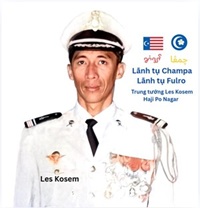

In the power structure of the Royal Government of Kampuchea, the participation of ethnic minority communities is an important factor reflecting the level of inclusivity, social harmony, and political stability of a multi-ethnic state. In this overall picture, the Cham people represent a community with a long history, having experienced profound upheavals yet still maintaining their presence and gradually establishing a certain position in political and social life as well as within the state apparatus of Kampuchea. Examining the role and position of the Cham people within the power structure not only has historical significance, but also helps clarify how the Royal Government of Kampuchea manages ethnic diversity and strengthens social cohesion. From a historical perspective, the Cham community in Kampuchea has been present from the early period of the national power system, particularly through individuals holding positions in the military and central government prior to 1975. The most prominent example is Lieutenant General Les Kosem, a senior Cham officer in the Royal Khmer Armed Forces. The fact that a Cham individual reached the rank of general in the army during this period shows that the Cham community was not only present on the margins of society, but also participated in the military leadership of the country. |

Trong cấu trúc quyền lực của Chính phủ Hoàng gia Kampuchea, sự tham gia của các cộng đồng dân tộc thiểu số là một yếu tố quan trọng phản ánh mức độ bao dung, hòa hợp và ổn định của một nhà nước đa dân tộc. Trong bức tranh đó, người Cham là một cộng đồng có lịch sử lâu dài, từng trải qua nhiều biến động sâu sắc nhưng vẫn duy trì được sự hiện diện và từng bước xác lập vị thế nhất định trong đời sống chính trị, xã hội và trong bộ máy nhà nước Kampuchea. Việc xem xét vai trò và vị thế của người Cham trong cấu trúc quyền lực không chỉ có ý nghĩa về mặt lịch sử, mà còn giúp làm rõ cách thức Chính phủ Hoàng gia Kampuchea quản lý sự đa dạng dân tộc và củng cố đoàn kết xã hội. Xét trên bình diện lịch sử, người Cham Kampuchea đã có sự hiện diện từ giai đoạn đầu trong hệ thống quyền lực quốc gia, đặc biệt thông qua các cá nhân giữ vị trí trong quân đội và chính quyền trung ương trước năm 1975. |

Following the 14th Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam, the newly elected Central Committee was announced, comprising 200 members, of which 11 were identified as belonging to ethnic minority groups, accounting for approximately 6.1% of the total membership. On a purely numerical level, this can be considered a certain degree of participation by ethnic minority communities in the Party’s highest leadership body. However, when analyzed in the context of historical institutional structures and power distribution, this representation reveals multiple systemic asymmetries. Among the 11 Central Committee members from ethnic minority groups, only one holds a position on the Politburo. This presence indicates that, in principle, access to the highest echelons of power is not entirely closed. Yet, the singular and non-recurring nature of this case demonstrates that it is an individual exception rather than a reflection of a stable, long-term representative mechanism. |

Sau Đại hội XIV của Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam, Ban Chấp hành Trung ương khóa mới được công bố gồm 200 ủy viên, trong đó 11 người được xác định thuộc các sắc tộc thiểu số, chiếm khoảng 6,1% tổng số ủy viên. Trên bình diện số liệu, đây có thể được xem là một mức độ tham gia nhất định của các cộng đồng sắc tộc thiểu số trong cơ quan lãnh đạo cao nhất của Đảng. Tuy nhiên, khi đặt trong phân tích lịch sử thể chế và cấu trúc quyền lực, bức tranh đại diện này bộc lộ nhiều bất cân xứng mang tính hệ thống. Trong số 11 Ủy viên Trung ương thuộc các sắc tộc thiểu số, chỉ có một người là Ủy viên Bộ Chính trị. Sự hiện diện này cho thấy khả năng tiếp cận tầng nấc quyền lực cao nhất về mặt nguyên tắc không hoàn toàn bị đóng lại. Tuy nhiên, việc trường hợp này mang tính đơn lẻ và không lặp lại qua các nhiệm kỳ cho thấy đây là ngoại lệ cá nhân, chứ chưa phản ánh một cơ chế đại diện ổn định, có khả năng tái tạo trong dài hạn. |

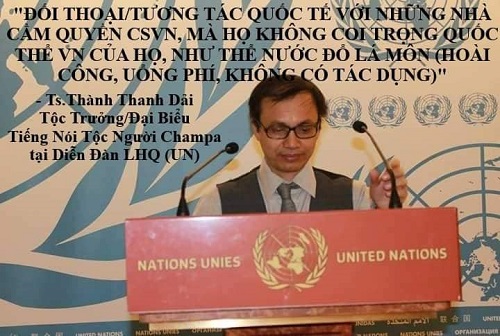

Modern Vietnam is not the product of a single historical path or a sole political actor. The country was formed on the foundation of at least three historically independent and sovereign political spaces: Đại Việt in the North, Champa in Central Vietnam, and Khmer Krom in the South. This is not a metaphor it is a historical reality that shaped Vietnam’s territory, population, and social structure. Yet, at the 14th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam, the nineteen members of the Politburo the highest decision-making body include no representatives from the Cham or Khmer Krom communities. Among approximately 200 Central Committee members, both full and alternate, their absence is comprehensive. If this had happened in a single term, it might be seen as coincidence. But when it occurs repeatedly over decades, it reveals a systematic, exclusionary power structure. This is no longer a question of “ethnic underrepresentation”; it is a state model built on political assimilation. Vietnam’s current power structure functions as a direct continuation of Đại Việt’s historical authority rather than a multi-historical political compact among the actors who created the nation. Within this system, coastal Champa in Central Vietnam is entirely absent from central politics. Highland Champa historical Vijaya in the Central Highlands appears only in politically neutral, softened forms. Khmer Krom in the South is excluded from the center of power altogether. |

Việt Nam hiện đại không phải là sản phẩm của một lịch sử đơn tuyến hay một chủ thể chính trị duy nhất. Quốc gia này được hình thành trên nền tảng của ít nhất ba không gian lịch sử, chính trị độc lập và từng có chủ quyền: Đại Việt ở phía Bắc, Champa ở miền Trung, và Khmer Krom ở Nam Bộ. Đây không phải là một ẩn dụ học thuật, mà là một thực tế lịch sử căn bản đã định hình lãnh thổ, dân cư và cấu trúc xã hội của Việt Nam ngày nay. Trong khoa học chính trị so sánh, các quốc gia hình thành từ nhiều không gian lịch sử như vậy thường đòi hỏi một cấu trúc quyền lực có tính bao trùm, phản ánh sự đa dạng của các chủ thể đã góp phần tạo nên quốc gia. Tuy nhiên, thực tiễn quyền lực trung ương tại Việt Nam cho thấy một xu hướng hoàn toàn ngược lại. Tại Đại hội XIV của Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam, trong mười chín (19) Ủy viên Bộ Chính trị, cơ quan quyền lực cao nhất của hệ thống chính trị không có bất kỳ đại diện nào đến từ cộng đồng Cham (Champa) hay Khmer (Khmer Krom). Trong khoảng hai trăm (200) Ủy viên Trung ương Đảng, bao gồm cả chính thức và dự khuyết, sự vắng mặt này cũng mang tính toàn diện. |

Trong các quốc gia theo thể chế tự do dân chủ, quyền lập hội được thừa nhận như một quyền căn bản của công dân. Pháp luật cho phép một số cá nhân đứng ra thành lập các hội đoàn xã hội hoặc chính trị, với điều kiện sinh hoạt ấy không trái với luật pháp sở tại. Mục đích của quy định này là bảo đảm tự do tư tưởng và quyền sinh hoạt tập thể, chứ không nhằm thiết lập tư cách chủ quyền hay trao thẩm quyền đại diện chính trị cho bất kỳ cộng đồng dân tộc nào. Quyền lập hội và quyền đại diện dân tộc là hai phạm trù thuộc những bình diện khác nhau. Quyền lập hội thuộc lãnh vực dân sự; quyền đại diện dân tộc thuộc lãnh vực công quyền. Sự phân biệt này là một nguyên lý nhập môn của lý luận chính trị hiện đại. Việc đồng nhất hai phạm trù ấy không chỉ là một nhầm lẫn khái niệm, mà còn dẫn tới những hệ quả chính trị khó lường. Tuy nhiên, trong sinh hoạt của một bộ phận người Cham ở hải ngoại hiện nay, ranh giới căn bản này đang bị hiểu sai, hoặc bị cố ý làm mờ. |

Nhân thời khắc chuyển giao giữa năm cũ và năm mới, thay mặt Tổng Ban Biên tập Báo Điện tử Champa.one, tôi xin gửi lời tri ân chân thành đến quý độc giả, cộng tác viên và bạn bè gần xa đã đồng hành, tin tưởng và ủng hộ trong suốt năm 2025. Năm vừa qua mang nhiều thử thách, nhưng cũng là dịp khẳng định vai trò của Champa.one trong việc: Bảo tồn và lan tỏa văn hóa Champa; Tôn trọng và truyền tải sự thật lịch sử; Lắng nghe và phản ánh trung thực tiếng nói của các cộng đồng bản địa. Bước sang năm 2026, chúng tôi cam kết tiếp tục nâng cao chất lượng nội dung, giữ vững chuẩn mực báo chí, và đóng góp tích cực vào việc bảo vệ di sản, lịch sử và bản sắc văn hóa Champa. Kính chúc quý độc giả và gia đình một năm mới bình an, sức khỏe, trí tuệ, và thịnh vượng. Mong rằng năm mới sẽ mang đến nhiều cơ hội hợp tác, phát triển, và sự lan tỏa mạnh mẽ hơn nữa của văn hóa Champa trên toàn cầu. California, Hoa Kỳ – Thời khắc chuyển giao năm 2025–2026 |

Every year, the Cham Ahier community (Cham who worship Po Allah and are still influenced by indigenous Hindu beliefs) continues to maintain many traditional rituals at the Po Klong Mah Nai Temple, which venerates Po Klong Mah Nai, Queen Bia Som, and the Cham secondary consorts. However, the information released by the Binh Thuan Department of Culture claiming that Po Klong Mah Nai was the last king of Champa and that his royal treasures are preserved in the home of Ms. Nguyễn Thị Thềm, presented as a descendant and the “last princess” of the Cham people, is inaccurate. Po Klong Mah Nai reigned from 1622 to 1627, while Ms. Nguyễn Thị Thềm was born in 1911 and passed away in 1995, nearly three centuries later. She may be descended from officials of the Thuận Thành district appointed by the Nguyễn dynasty in the early 19th century, but she has no blood relation to the Churu or Raglai royal lineages of Po Klong Mah Nai and Po Rome. |

Po Klong Mah Nai, also known as Po Mah Taha with the Islamic title Maha Taha, reigned over Panduranga from 1622 to 1627 and was one of the central figures in the history of seventeenth-century Panduranga-Champa. Numerous French scholarly sources classify him among the Muslim rulers, reflecting the significant role of Islam within the political and social structure of the Panduranga court. Born in Panduranga-Champa and deceased at Bal Canar (Parik-Panduranga), an area that today belongs to Phan Rí-Binh Thuan, Po Mah Taha was of Churu and Raglai ethnicity and had no blood ties to the Po Klong Halau dynasty (1579-1603), a royal line that exerted strong influence from the latter half of the sixteenth century to the early seventeenth century (Aymonier, 1890). According to the Panduranga chronicles (Sakkarai dak rai patao), he ascended the throne in the Year of the Dog and abdicated in the Year of the Cat, ruling for six years with the capital located at Bal Canar. In Nguyễn-dynasty Sino-Nom texts, his name was transcribed as Bà Khắc-Lượng Như-Lai, a Sinicized form of his original Cham appellation. Po Klong Mah Nai (1622–1627) passed the throne to Po Rome (1627–1651). Po Rome was a king of Panduranga–Champa who adhered to and revered Islam. |