Abstract

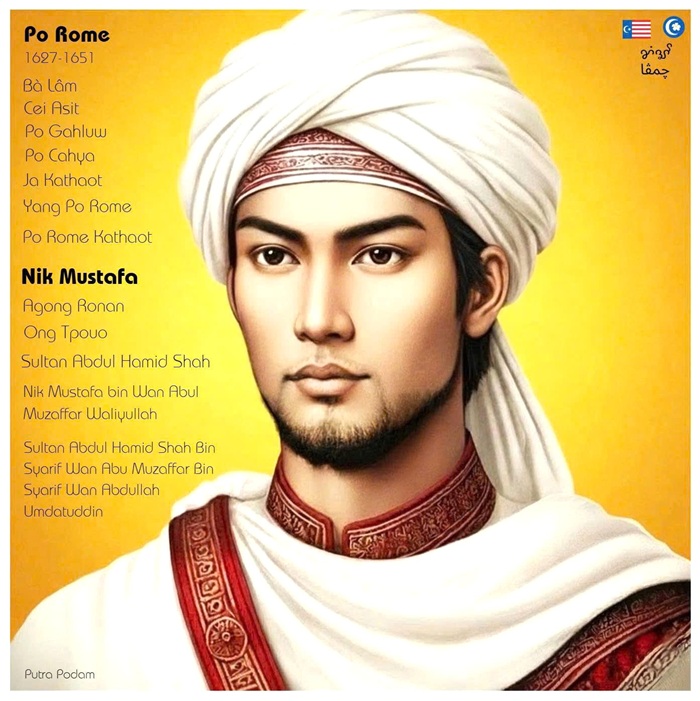

The research focuses on the life, origins, political policies, and cultural, religious legacy of King Po Rome (1627-1651), one of the most prominent rulers of the Panduranga-Champa principality in the seventeenth century. Drawing on historical sources such as the Cham chronicle Sakkarai dak rai patao, Kelantan royal genealogies (Malaysia), diplomatic records involving Đại Việt, Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora, as well as modern scholarly studies on Champa and Southeast Asia, the study analyzes Po Rome as a model of cultural and religious convergence.

Po Rome is recorded as the ruler of Panduranga-Champa who advanced the Islamization process while maintaining traditional indigenous beliefs. He constructed an Islamic mosque at the capital Bal Pangdurang and developed architectural structures characteristic of Cham civilization, while simultaneously preserving local ritual practices. This combination reflects his policy of religious conciliation, the preservation of Cham, Churu, Raglai, and Rhade cultural identities, and the integration of Islamic elements from Kelantan and Patani, thereby forming a unique model of a “religiously harmonious king” in Southeast Asian history.

The study elucidates various aspects of Po Rome’s family and lineage, in which Kelantan sources record him under the Islamic name Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah, and describe his three distinguished sons who assumed leadership roles in Champa, Patani, and Singgora. Through diplomatic and marital alliances with Kelantan, Po Rome strengthened religious and political networks between Champa and the Malay Peninsula’s Islamic world, while enabling Champa to maintain its independence amid pressure from Đại Việt and Ayutthaya.

Beyond his political and diplomatic significance, Po Rome is also regarded as a social reformer and protector of the populace, with legends emphasizing justice, care for the poor, and the protection of indigenous communities. His cultural and religious legacy remains vibrant today through certain ritual ceremonies, acts of veneration at temples and towers, and within the collective memory of the Cham community in Panduranga, as well as through the titles Wan, Nik, and Che in Kelantan.

The research concludes that Po Rome stands as a symbol of civilizational convergence and a testament to the capacity for religious harmony, ethnic identity preservation, and diplomatic expansion in the context of seventeenth-century Southeast Asia. The study not only clarifies Po Rome’s historical role but also contributes to identifying the multilayered cultural and religious values of Panduranga-Champa during the final phase of its independence.

Từ khóa (Keywords): Po Rome, Champa, Panduranga, Churu (Cru), Balamon (Hinduism), Southeast Asian Islam, Cultural-religious syncretism, Kelantan, Patani, Southeast Asian history, Cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

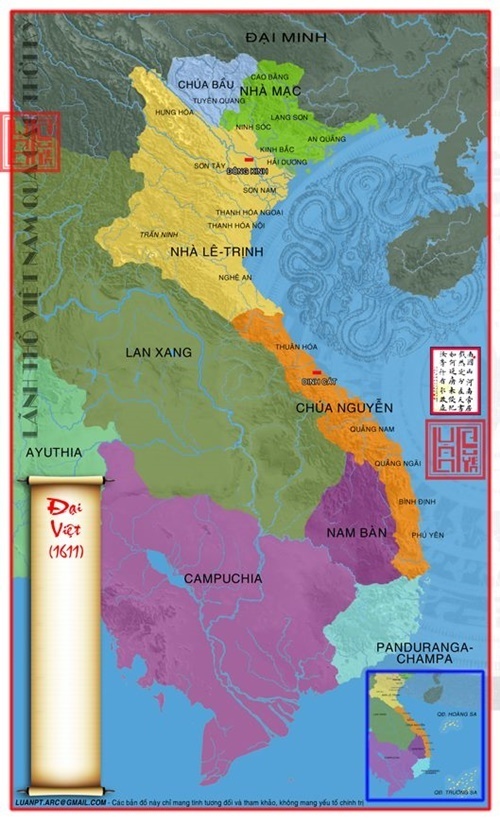

1.1. Historical Context of Panduranga

The seventeenth century marked a challenging period for the independent kingdom of Champa, with its political center concentrated in Panduranga, corresponding to the present-day regions of Ninh Thuận, Bình Thuận, and part of Lâm Đồng. After centuries of territorial decline due to continuous wars with Đại Việt, coupled with internal conflicts and factionalism within the royal family, Panduranga-Champa entered a period in which political, religious, and cultural factors were not merely social or political elements but became crucial tools for preserving ethnic identity and consolidating royal authority.

Under Po Rome, Panduranga functioned as a multi-ethnic principality where indigenous beliefs continued to exert influence alongside the vigorous spread of Islam, which was transmitted through merchant networks and diplomatic relations with Islamic centers in the Malay Peninsula, Kelantan, and Patani. The integration of indigenous beliefs influenced by Hinduism into Agama Ahier (late Islam) alongside Agama Awal (early Islam) under the shared worship of Allah served as a key political strategy aimed at fostering unity, ensuring social stability, and enhancing the prestige of the royal court within a Southeast Asia increasingly shaped by the spread of Islam from Vijaya-Champa since the fourteenth century under King Che Bunga (Chế Bồng Nga), when Islam had become the state religion.

In this context, Po Rome (reigned 1627-1651) emerged as a central figure in Panduranga, serving both as a sovereign wielding political authority and as a cultural and religious symbol of the kingdom. He not only consolidated governmental order and maintained traditional religious rituals but also extended his influence beyond the borders, establishing political and religious relations with Islamic centers on the Malay Peninsula and in Patani. It was precisely the harmony between indigenous beliefs and Islam, combined with the ability to construct a flexible government closely connected to the community, that rendered Po Rome a defining figure in the history of Panduranga-Champa.

The seventeenth-century historical context of Panduranga-Champa thus reflects not only territorial decline and political tension but also cultural and religious adaptability, where traditional and Islamic elements intersected to shape the distinctive leadership, diplomatic, and religious strategies of Panduranga under Po Rome.

1.2. Research Problem

Research on Po Rome, the prominent seventeenth-century king of Panduranga, faces significant challenges due to the coexistence of multiple sources of information, each possessing distinct characteristics, purposes, and contexts.

1.2.1. Champa Historical Records

The Panduranga chronicles (Sakkarai dak rai patao) record that Po Rome ascended the throne in the Year of the Rabbit and reigned for approximately 24-25 years, with his capital at Biuh Bal Pangdurang. These historical sources focus primarily on political and administrative aspects, such as the consolidation of royal power, the construction of towers and religious monuments, and the maintenance of indigenous beliefs alongside Islamic rituals. Information in these chronicles is often official in nature, emphasizing activities that reflect authority and the preservation of social and religious order, while providing limited details about personal life, familial relationships, or legendary elements associated with the figure.

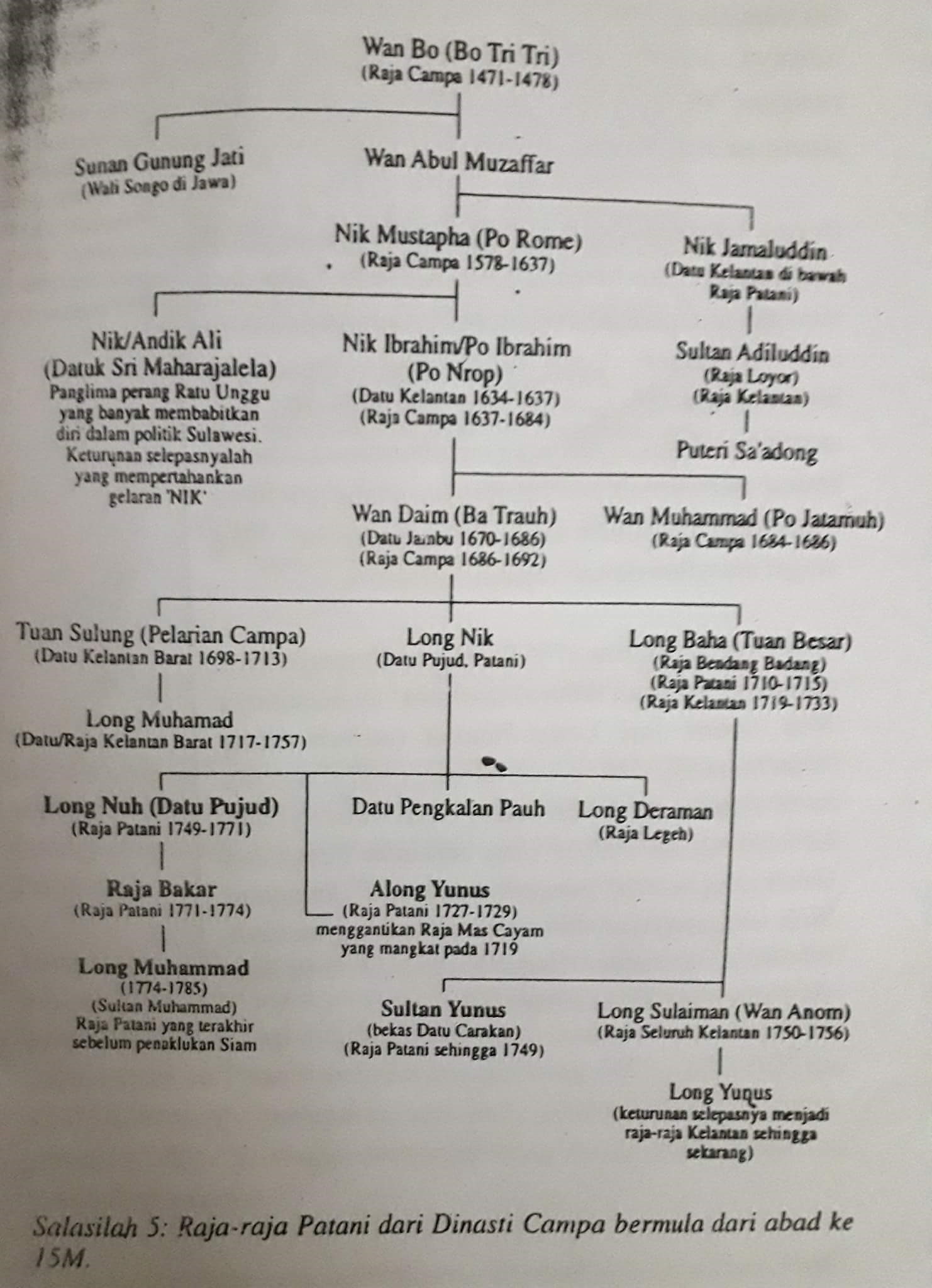

1.2.2. Genealogies in Kelantan-Malaysia

In the genealogies and historical records of the Kelantan and Patani royal families, Po Rome is known by his Islamic name, Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah, born into the noble Nik and Wan lineages. This stream of information highlights religious and political connections between Champa and Southeast Asian Islamic kingdoms, particularly Kelantan and Patani. The Malaysian genealogies not only document Po Rome’s lineage and ancestry but also describe the roles of his sons in regional Islamic centers, reflecting the broader dissemination of Panduranga’s political and religious influence beyond its borders.

1.2.3. Cham Folk Legends

Beyond official chronicles and foreign genealogies, Cham folk traditions preserve numerous legendary elements concerning Po Rome’s origins, his connections to the Churu ethnic group, and the temples and rituals associated with his name. These legends are often symbolic, reflecting religious beliefs, cultural values, and community perceptions of royal authority, while also preserving traditional cultural values across generations.

The divergence among these sources-official Champa records, Malaysian genealogies, and Cham folk legends-presents a significant research challenge: how to systematically synthesize and cross-reference these sources, assess their authenticity, and identify the cultural, religious, and political significance of Po Rome within a broader historical context. Addressing this challenge not only contributes to reconstructing an accurate historical portrait of Po Rome but also provides deeper insights into cultural and religious interactions in Panduranga and seventeenth-century Southeast Asia.

1.3. Research Methodology

This study employs an interdisciplinary approach, integrating history, culture, and archaeology to construct a comprehensive picture of the life, career, and legacy of Po Rome. Specifically:

1.3.1. Analysis of Champa Historical Records

The research examines primary chronicles such as Sakkarai dak rai patao, related Sino-Vietnamese documents, and diplomatic records with Đại Việt. Reading, translating, and comparing these sources help reconstruct the political and social context, major events during the Panduranga reign, and the role of Po Rome in regional relations.

1.3.2. Analysis of Malaysian Genealogies

Materials from Kelantan and Patani, including the Nik and Wan genealogies, seventeenth-century manuscripts, and studies by Malay and Thai historians, are analyzed to identify royal lineage, blood relations, and political marriages. This method also elucidates the network linking Champa with Southeast Asian Islamic kingdoms.

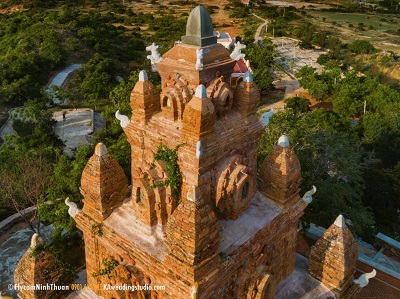

1.3.3. Ethnography and Archaeology

Field surveys of religious sites and architecture, such as the Po Rome tower, Yang Thaok temple, the Kate festival, and contemporary Cham Panduranga rituals, are conducted. This approach examines material traces, religious symbols, and enduring cultural and religious practices, reflecting the interplay between political authority and religion.

1.3.4. Interdisciplinary Comparison and Synthesis

The study synthesizes three main streams of data-historical records, royal genealogies, and folk legends-to analyze and integrate information, thereby identifying the historical, political, religious, and cultural role of Po Rome within the context of seventeenth-century Panduranga and Southeast Asia.

This methodology ensures both historical accuracy and the extraction of cultural and social significance, highlighting Po Rome as a symbol of harmonious governance and cultural synthesis in the history of Champa.

1.4. Research Objectives and Scope

1.4.1. Research Objectives

This study aims to provide a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the life, career, and legacy of Po Rome, the prominent seventeenth-century king of Panduranga. The specific objectives include:

To analyze the life and career of Po Rome within the political, social, and diplomatic context of seventeenth-century Champa, highlighting his role in consolidating power and governing the kingdom.

1. To clarify the origins and royal lineage of Po Rome, particularly his connections with the dynasties of Kelantan (Malaysia), Patani, and Singgora (Thailand), in order to explain the diplomatic, political marriage, and regional mobility aspects of his life in Southeast Asia.

2. To study Po Rome’s role in reconciling religions in Panduranga-Champa, especially between indigenous beliefs and Islam, while assessing the enduring cultural and religious influences, including rituals, religious architecture, and folk traditions.

3. To evaluate Po Rome as a symbol of harmonious and reconciliatory governance, where civilizations, religions, and cultures intersect, thereby identifying models of flexible and adaptive leadership in the history of Champa.

1.4.2. Research Scope

The study focuses on the historical, cultural, and religious aspects of Po Rome within specific spatial and temporal boundaries:

Spatial scope: The principality of Panduranga-Champa (present-day Ninh Thuận, Bình Thuận, and part of Lâm Đồng provinces), as well as areas related to the royal family’s diplomatic and genealogical connections, including Kelantan (Malaysia), Patani, and Singgora (Thailand).

Temporal scope: The main focus is on the seventeenth century, particularly the period 1627-1651 during Po Rome’s reign, while referencing earlier historical events to clarify the political, social, and traditional relations of the Champa royal court.

Content scope: The study emphasizes analysis of historical records, royal genealogies, folk legends, archaeology, religious symbols, and cultural and religious studies, aiming to provide a comprehensive portrayal of Po Rome’s life, role, and legacy.

2. Sources and Academic Foundations

In studying King Po Rome, identifying and analyzing relevant sources is a crucial step. The main sources include Champa historical records, Cham folk legends, Kelantan royal genealogies, Malay, Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora historical manuscripts, as well as modern academic studies.

2.1. The Sakkarai dak rai patao Chronicle

The Sakkarai dak rai patao chronicle is the most important primary source from Panduranga documenting Po Rome’s reign. According to this chronicle, Po Rome ascended the throne in the Year of the Rabbit and ruled for approximately 24-25 years, with his capital at Biuh Bal Pangdurang (the Panduranga citadel).

The chronicle provides essential information regarding: the royal succession order and relations with Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), his predecessor and father-in-law; construction activities, particularly the Po Rome tower and Islamic shrines, reflecting policies of religious integration; and records of rituals, cremation ceremonies, and worship practices, which form a basis for studying the coexistence of indigenous beliefs and Islam in Panduranga-Champa.

However, the chronicle primarily focuses on political and religious events and provides limited insight into everyday life, necessitating the integration of other sources for a comprehensive understanding.

2.2. The Ariya Po Rome Texts and Cham Folk Legends

The Ariya Po Rome texts constitute a body of epic poetry, narrative verse, and Cham folk legends, primarily transmitted in Thrah (Srah) script and regional language variants in Panduranga. The Ariya represents a traditional Cham literary genre with educational purposes, praising virtue, heroic qualities, and simultaneously documenting rituals, customary law, and social knowledge. The Ariya texts on Po Rome focus on reconstructing the life, deeds, and cultural-religious persona of the king, while also preserving mythological and folk elements that existed alongside official chronicles.

A particularly important aspect of the Ariya Po Rome is the legend of the king’s birth. According to several versions, Po Rome’s mother was abandoned or compelled to leave her family due to connections with the Churu people and gave birth to Po Rome in the village of Pa-aok (Tường Loan, Bắc Bình district, Bình Thuận province). The Ariya describe in detail the miraculous gestation, Po Rome’s exceptional appearance and demeanor, and the sacredness of the king from an early age, evidenced by miraculous signs or omens in the folk narrative. These details are largely absent in the official chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao) but play a crucial role in shaping the communal imagination of Po Rome.

Additionally, the Ariya Po Rome records narratives highlighting the king’s heroism, social justice, and moral virtues. Stories recount Po Rome defending villages from external threats, caring for the poor, mediating internal disputes, and maintaining social peace. These accounts reflect both the political ideals of a Panduranga-Champa king and the role of the monarch as a religious center and ethical symbol within the community. Many Ariya emphasize the king’s connection to religious rituals, such as the Kate festival, rain-seeking ceremonies, and ancestor veneration, demonstrating the interrelationship between royal authority, religion, and popular life.

Folk legends and Ariya texts also provide supplementary information absent in the official chronicles, such as traditional funerary rituals and details of the daily life of the king and queen. Po Dharma, emphasizes that studying the Ariya Po Rome is essential to fully understanding Po Rome’s image in the Cham collective memory, how the king was revered, and the role of folk literature in preserving history, reinforcing ethnic identity, and maintaining indigenous religious traditions.

The Ariya Po Rome thus serves not only as a literary source but also as a critical historical and anthropological resource, enabling researchers to access aspects of Cham life, belief systems, and culture that official chronicles sometimes fail to capture. It demonstrates that Po Rome was both a historical monarch and a cultural-religious symbol, remembered and venerated by the Panduranga community across generations.

2.3. Kelantan Royal Genealogies and the Title “Nik”

In Kelantan, Malaysia, the Malay royal genealogies record Po Rome with his full Islamic name as Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah. These genealogies are considered a crucial source for studying the political, religious, and cultural relations between Champa and the Islamic centers of the Malay Peninsula, including Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora. According to Abdul Rahman Tang Abdullah, these genealogies not only provide information on lineage but also reflect the networks of power and religious influence across the region in the seventeenth century.

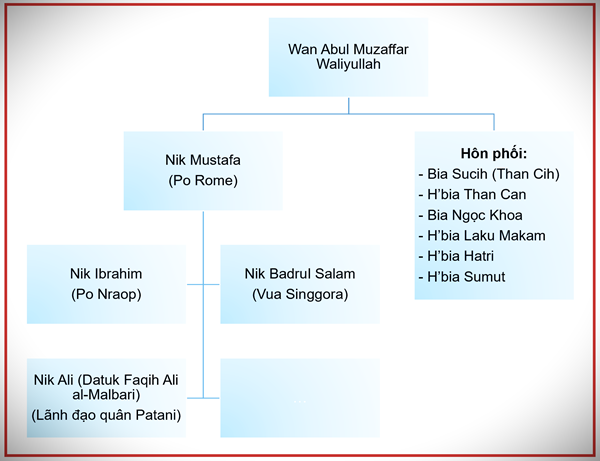

The Kelantan genealogies detail the descendants and sons of Po Rome, clarifying political and religious connections among Islamic royal families:

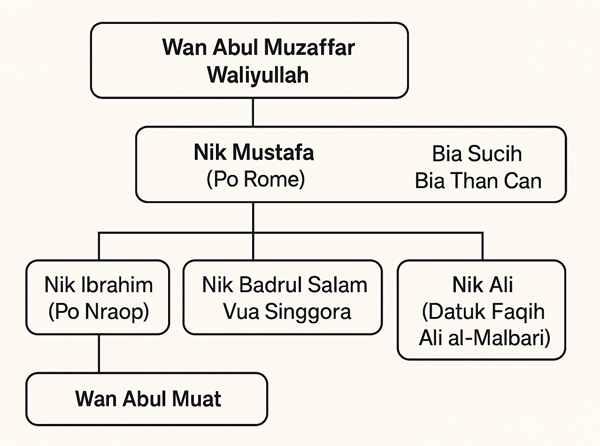

Nik Ibrahim (Po Nrop or Po Nraop), the eldest son, became the direct successor in Panduranga, maintaining the royal authority and continuing Po Rome’s political traditions in Champa. However, Vietnamese sources suggest that Po Nrop was a half-brother of Po Rome.

Nik Badrul Salam ascended as king of Singgora (southern Thailand), illustrating the expansion of Champa royal influence and power to island-based Islamic centers, linking Champa with Malay administrations in the Gulf of Thailand.

Nik Ali (Datuk Faqih Ali al-Malbari) led the Patani army, reflecting Po Rome’s military and political role within the Southeast Asian Islamic alliance network. Nik Ali is also mentioned as a religious leader who combined military command with the propagation of Islam, demonstrating the dual role of the royal family in both political and religious spheres.

The title “Nik” in the Malay royal system is traditionally conferred on those belonging to Islamic royal lineages, signifying authority, prestige, and religious leadership. According to Po Dharma, this title is not merely a political designation but also a religious symbol, emphasizing the role of the bearer in protecting the Muslim community, overseeing rituals, and managing land. In the case of Po Rome, being recorded with the title “Nik” in the Kelantan genealogies reflects the king’s cultural and religious integration into the Malay Peninsula Islamic network and affirms his status as a central figure of political and religious authority across the region.

The genealogies also reveal connections between the Nik and Wan families, with Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah, Po Rome’s father, bestowing the title “Nik” upon his son, symbolizing the linkage between royal power and Islamic faith. This illustrates the unification of political and religious authority, enabling Po Rome to consolidate his rule in Champa while extending influence to neighboring Islamic centers. Research by Nara Vija emphasizes that these genealogies also demonstrate how Malay Islamic dynasties recognized interregional relations and royal authority, providing a framework to compare with the Champa chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao) to gain a deeper understanding of Po Rome’s position within the seventeenth-century Southeast Asian context.

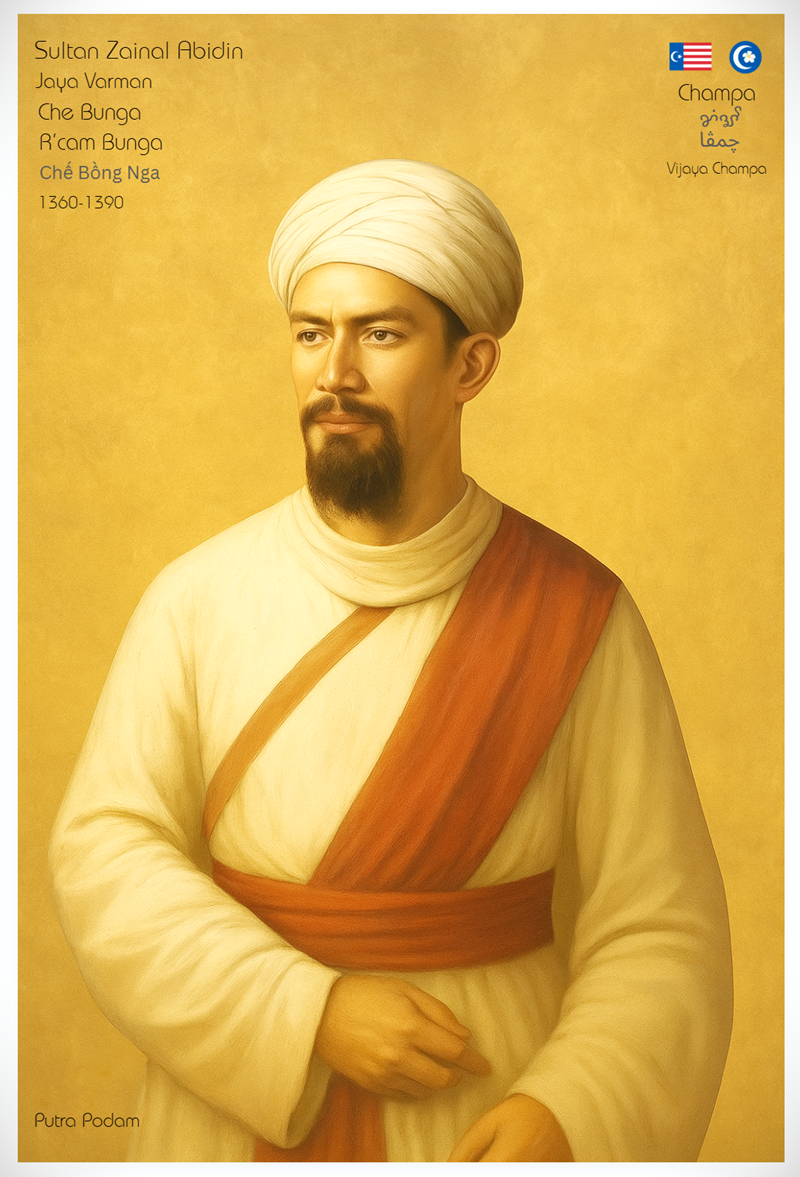

Figure 1. Direct lineage diagram of King Po Rome (Nik Mustafa). Photo: Putra Podam.

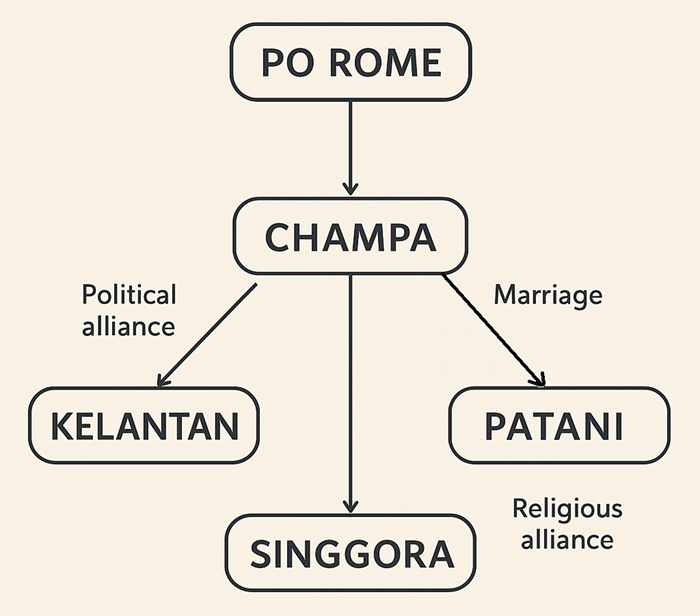

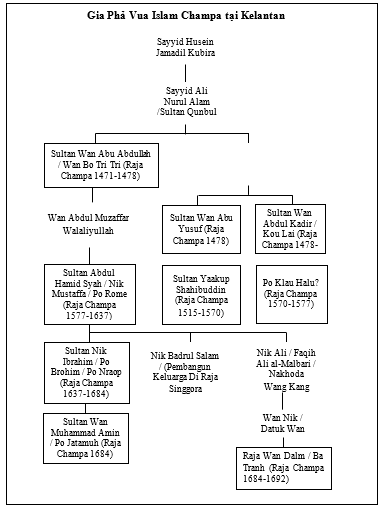

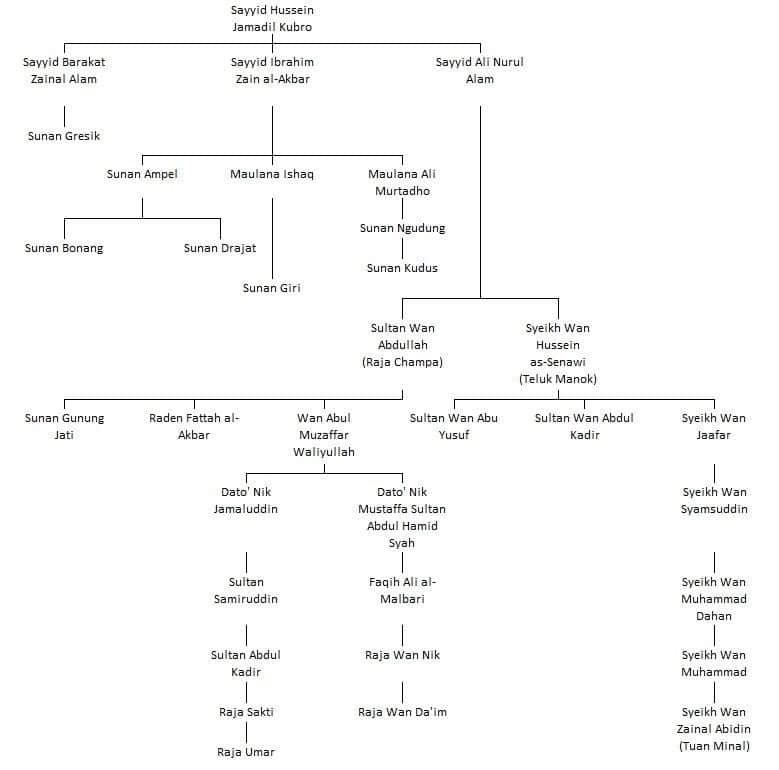

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating Po Rome as a central connecting figure across generations, both a king of Champa and a member of the Malay Islamic royal lineage, while also serving as a political, religious, and cultural bridge linking Panduranga, Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora. Photo: Putra Podam.

2.4. Malay, Patani, and Singgora Historical Sources

Historical sources from Malaysia, Patani, and Singgora provide an important supplementary perspective on Po Rome, the prominent seventeenth-century king of Champa, while also revealing the complex interactions between Champa and the Islamic centers of the Malay Peninsula. These sources, primarily recorded in Jawi script, Malay language, and occasionally in Thai script, document not only political events but also cultural and religious expressions associated with this figure. In conducting research, these sources require careful translation and cross-referencing with Champa materials to ensure both accuracy and comprehensiveness.

From the Malay and Patani records, it is evident that Po Rome actively established political and religious alliances through marriage and familial ties, thereby consolidating Champa’s position within the Southeast Asian Islamic power network. His travels and presence in centers such as Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora were not solely diplomatic but also involved participation in religious ceremonies, indicating that he held both political and spiritual authority. Through his sons and descendants, these alliances were maintained sustainably, allowing Po Rome to create a system of relations extending beyond the borders of Champa, while simultaneously reinforcing the role of his lineage within the regional political and religious network.

Beyond political aspects, these sources also record rituals, legends, and miraculous accounts related to Po Rome, reflecting the ways in which the Malay and Patani communities remembered and honored him. Folklore, commemorative rituals, and other cultural expressions transmitted across generations demonstrate that Po Rome’s influence extended beyond political power to encompass significant cultural and religious dimensions. He became a historical and religious symbol whose legacy contributed to the formation of collective memory and cultural identity beyond the territory of Champa.

The study of Malay, Patani, and Singgora sources requires a rigorous methodological approach, combining precise translation with meticulous cross-referencing to Champa sources. Only through such an approach can the true role of Po Rome within the Southeast Asian alliance network be accurately identified, while also explaining his enduring presence in the cultural memory and practices of Malay and Patani communities.

Figure 3. Diagram of Po Rome forming alliances with centers such as Champa, Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora, enabling him to maintain long-term stability and establish a network of relations extending beyond the borders of Champa, while simultaneously strengthening the role of his lineage within the regional political and religious network. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 4. King Po Rome (Che Rome, Nik Mustafa, Sultan Abdul Hamid Shah, Nik Mustafa Bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah). He was the king of Panduranga-Champa. Photo: Putra Podam.

3. Legends and Myths about the Origins of Po Rome

Legends and myths play a crucial role in shaping the image of Po Rome in Cham folk memory. These narratives not only reflect cultural and religious origins but also highlight the connections between Champa and indigenous groups such as the Churu.

According to tradition, after consuming the leaves of the liem tree (phun kraik), a young woman in Panduranga-Champa became pregnant despite not having a husband. Upon hearing this, her family expelled her from her home in Ra-njaoh village, which was located across a vast area stretching from the Sông Mao railway station to Banâk Patau Ceng (Đập Đá Hàn) in Bắc Bình, Bình Thuận. In Pa-aok village, known to the Vietnamese as Tường Loan, she gave birth to a handsome and robust baby boy, who was named Ja Kathaot.

Another tradition holds that Po Rome’s mother befriended a Churu companion, but her parents and lineage did not approve, forcing her to leave the village while pregnant. After Po Rome was born, his placenta was buried in Pa-aok, now the Tường Loan village, in the Hòa Thuận Catholic hamlet. The site of Po Rome’s placenta burial was later venerated by the local Cham community, who established a shrine called Yang Thaok Po Rome. This shrine is located alongside the road from the Bình Thuận Cham Museum (Phan Hiệp) to Sông Mao, approximately one kilometer from the museum.

Figure 5. The Yang Thaok Po Rome Temple, located in Pa-aok village (Tuong Loan village within the Hoa Thuan Catholic parish), Binh Thuan Province. Photo: Putra Podam.

The third legend emphasizes that Po Rome’s mother was a Cham royal who loved a Churu man, and because her lineage did not accept this union, she traveled and stayed in the Cham village fields of palei Pabhan (Vụ Bổn village, Phước Ninh commune, Thuận Nam district, Ninh Thuận province). Later, the local people built the Po Rome Kathaot shrine at this site.

Together, these three legends indicate that Po Rome had Cham-Churu origins, blending indigenous culture with royal lineage, while highlighting miraculous elements, trials, and the power of birth-a common motif in Southeast Asian cultural narratives.

The Po Rome legends reflect a widespread cultural structure in Southeast Asia, where heroic figures often emerge from unusual or divinely challenged circumstances, such as unintended pregnancies or social rejection, yet are under the protection of the divine, giving birth to extraordinary children endowed with exceptional strength, intelligence, or destiny. In Po Rome’s case, these elements are manifested through his difficult beginnings, societal rejection, birth at the sacred site of Pa-aok village, and upbringing at palei Pabhan, both linked to shrines and rituals maintained by the community to this day. This mythological structure underscores divine authority and royal destiny while creating an image of a king who is both accessible to the people and yet transcendently extraordinary.

The locations associated with Po Rome carry significant symbolic meaning. Palei Pa-aok (Tường Loan village, Bình Thuận) is not only his birthplace but also the site of his placenta burial, becoming a focal point for Cham community worship. Palei Pabhan (Vụ Bổn, Phan Rang) was the temporary residence of Po Rome’s mother and later became the site of the Po Rome Kathaot shrine. Yang Thaok Po Rome is the shrine marking the placenta burial, established by the Cham community to honor Po Rome’s origins and lineage. These locations are not merely physical sites but also cultural and religious symbols, emphasizing the connection between land, ancestors, and royal power in popular consciousness.

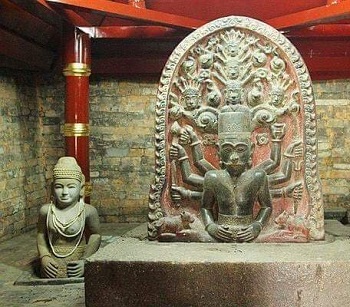

Material traces associated with Po Rome continue to exist and are maintained by the Cham Panduranga community today. The Po Rome tower at Bal Pangdurang, housing the Mukha Linga statue of Po Rome, represents the Cham Ahier adaptation, simultaneously continuing indigenous folk beliefs and emphasizing the king’s divine authority. Yang Thaok Po Rome shrine still hosts periodic rituals connected to placenta burials, while the Po Rome Kathaot shrine exemplifies religious syncretism, integrating indigenous beliefs with Islam from the royal court. The Kate festival and combined folk rituals reflect the persistence of Po Rome traditions in the contemporary community. These material traces and rituals confirm the continuity of Cham culture and demonstrate Po Rome’s role as a central figure in the intersection of culture, religion, and royal authority.

4. Po Rome in Malaysian Sources and the Champa-Kelantan Relationship

Malaysian sources provide important information about King Po Rome, complementing Champa records and clarifying the network of political and religious relationships in seventeenth-century Southeast Asia. The Kelantan royal genealogy records Po Rome under his full Islamic name, Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah (commonly called Nik Mustafa), emphasizing his familial connections with the Nik and Wan lineages, which had long-standing political and religious authority in Kelantan. This genealogy provides key information about Po Rome’s lineage, marital alliances, and the roles of his sons in the Islamic centers of Patani and Singgora, while also reflecting how Po Rome leveraged royal authority to maintain regional political and religious networks.

The Malay royal title system includes designations such as Wan, Nik, Ku, Che, each indicating social status, roles, and religious affiliation. The title “Nik” was conferred upon members of the Islamic royal lineage, signifying legitimate power, ties with religious scholars, and reinforcing prestige within the Muslim community. In contrast, the Cham prefix “Che” reflects indigenous royal authority, rooted in Champa tradition, with both political and religious symbolism. Comparing the gelaran “Che” in Champa with “Nik” in Kelantan shows functional similarities in affirming royal authority, though they derive from different cultural and religious foundations. The title “Che” is locally grounded and associated with Islam in Champa, while “Nik” is connected to Islam and Southeast Asian religious networks.

Po Rome’s lineage included three prominent princes, each holding distinct political and religious roles, reflecting the Panduranga court’s strategy for extending influence. Nik Ibrahim (Po Nrop) continued internal authority within Champa, maintaining royal rituals and dynastic power at Panduranga, while reinforcing legitimacy for subsequent generations. Nik Badrul Salam became king of Singgora in southern Thailand, serving as a diplomatic and religious bridge between Champa and Southeast Asian Islamic centers, ensuring trade and regional security. Nik Ali (Datuk Faqih Ali al-Malbari) commanded the Patani military, playing a key role in defending religious alliances and expanding Champa’s strategic influence over Islamic centers. This lineage illustrates how Po Rome combined internal power with regional networks, using marriage, kinship, and royal titles to consolidate political and religious authority.

The relationship between Champa, Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora was based not only on bloodlines but also on religious and commercial connections. As both King of Champa and a member of the Nik lineage, Po Rome enabled Panduranga to participate in the Islamic trade network, facilitating the exchange of goods, knowledge, and culture with the Malay Peninsula. Islamic centers such as Patani and Singgora became strategic allies, supporting Champa in maintaining relative independence amid pressures from Đại Việt and Ayutthaya, while reinforcing the presence of Islam within the Panduranga kingdom.

A synthesis of genealogical data and Malay, Patani, and Singgora sources shows that Po Rome was not merely a Champa king but also an architect of a regional religious and commercial network, harmonizing indigenous Cham folk traditions with Malay Peninsula Islam. By connecting royal lineages, establishing alliances with Patani and Singgora, and maintaining traditional rituals and beliefs, Po Rome exemplifies the capacity to integrate political, religious, and cultural authority in seventeenth-century Southeast Asia.

Figure 6. Royal genealogy of King Po Rome (Nik Mustafa) in Kelantan, Malaysia.

Figure 7. Salasilah Kesultanan Islam Champa-The genealogy of the Champa kings in Kelantan.

Figure 8. Genealogy of the Islamic Champa lineage within the royal family in Kelantan, Malaysia.

5. Islamization and Royal Politics in Champa (10th-19th Centuries)

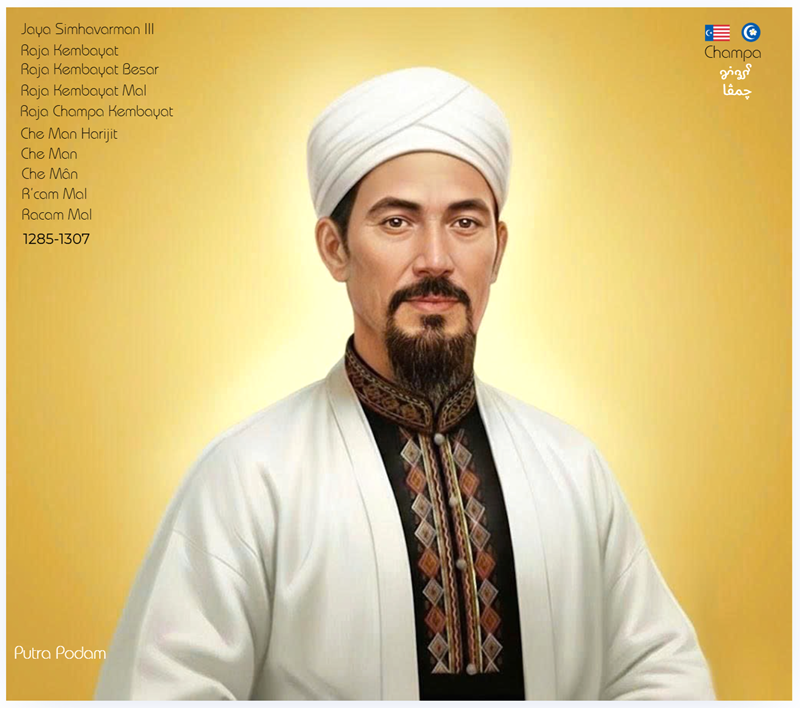

This section analyzes the relationship between Islam and royal authority in Champa from the 10th century until the kingdom’s collapse in the early 19th century. The process of Islamization was long-term and uneven, closely linked to political strategies, diplomatic marriages, and trade with neighboring Islamic polities such as Majapahit, Kelantan, Patani, Terengganu, Pahang, Melaka, and key Southeast Asian ports. The adoption of Islam allowed Champa kings to consolidate internal authority, enhance international status, and manage relations with indigenous beliefs. Champa rulers-from Po Aluah (Yang Puku Vijaya Sri), Po Krung Garai (Jaya Indravarman IV), Chế Mân (Jaya Simhavarman III or Raja Kembayat), Chế Bồng Nga (Sultan Zainal Abidin, Che Bunga), Po Rome (Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah) to Po Phaok The (Nguyễn Văn Thừa)-used Islam as a flexible tool in governance and diplomacy. They maintained a balance between Islam and traditional religions, establishing a distinctive political and religious model. Islam became a central factor shaping Champa’s power structure, culture, and society, reflecting the royal family’s adaptability and creativity in religious and political policy. It also strengthened diplomatic networks, expanded trade, and enhanced regional influence. Consequently, Champa retained strategic significance in Southeast Asia, even amid internal and external pressures. By the reign of Po Phaok The, royal Islamization became closely associated with the kingdom’s decline, marking a critical chapter in which Islam functioned not only as a religion but also as a decisive factor in Champa’s politics, diplomacy, and culture.

5.1. The Process of Champa Royal Islamization: From Po Aluah to Chế Bồng Nga

The Islamization of the Champa royal family from the 10th to the 14th century was a long-term and systematic historical process, reflecting Champa’s ability to harmonize indigenous beliefs with foreign religious elements while using Islam to reinforce political, diplomatic, and cultural authority. The emergence of Islam in Champa was neither abrupt nor isolated; it resulted from continuous cultural, commercial, and religious exchanges with Arab and Persian merchants and scholars, as well as with Muslim communities in Malayu, Java, and Sumatra. Champa’s strategic location along maritime routes connecting China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean facilitated the spread and development of Islam alongside indigenous religions, particularly Hinduism.

Yang Puku Vijaya Sri (Po Aluah, reign 998-1006) is recognized as the first Champa king to adopt Islam, marking a key milestone in royal Islamization. Born into the Jarai lineage, Po Aluah received Islam from Arab and Persian merchants and scholars and undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca, affirming his allegiance to the new faith and placing Islam at the center of power in Vijaya (Đồ Bàn, present-day Qui Nhơn). His reign witnessed the relocation of the Indrapura royal family to Vijaya for geographic convenience, reduced vulnerability to warfare, and consolidated political and religious power. Po Aluah was not only an administrative ruler but also a ritual organizer, integrating Islamic ceremonies with long-standing Hindu traditions in the Champa court, creating a multi-religious model of kingship. Chinese sources, especially the Song Shi, record that Champa subjects recited “Allahu Akbar” in sacrificial rituals, confirming the presence and practice of Islam in community life as early as the 10th century. This evidence demonstrates both the presence of Islam and Champa’s capacity to harmonize diverse beliefs in a multiethnic, multicultural environment.

Continuing this tradition, Jaya Indravarman IV (Po Krung Garai, 12th century) strengthened centralized power in Vijaya and maintained connections with Muslim communities in the Indian Ocean, including merchants from Java, Sumatra, and Melayu. He organized rituals combining Hindu and Islamic elements, preserving indigenous traditions while integrating new Islamic influences. Po Krung Garai is seen as a key link in the succession of Islamic rulers, extending religious influence into diplomacy, consolidating relations with neighboring Muslim principalities, and creating conditions for the long-term development of Islam within the Champa court. Under his reign, Vijaya became not only an administrative and military center but also a religious hub, where Islamic rituals and teachings were integrated with Hindu ceremonial practices, demonstrating Champa’s adaptability to social, economic, and cultural changes.

By the 13th century, Chế Mân (Raja Kembayat or Jaya Simhavarman III, reign 1285-1307) emerged as a prominent Islamic king in Champa’s middle period. Born in Vijaya to the Jarai-Rhade royal lineage, Chế Mân ascended the throne after Indravarman V’s death, adopting the regnal name Jaya Simhavarman III, and was called R’čam Mal by the Rhade and Jarai peoples. Ruling amid regional instability, Chế Mân maintained independence from Mongol invasions, expanded diplomatic relations with Đại Việt and the kingdoms of Java and Melayu, and integrated Islam into royal policy. Marriages with Muslim princesses from Java, Bhaskaradevi and Tapasi, as well as Đại Việt princess Huyền Trân, reinforced diplomatic alliances, facilitated the spread of Islam in the court, and demonstrated Champa as a multidimensional political and religious entity using royal marriage as a strategic instrument.

In architecture and ritual practice, under Chế Mân’s reign, Vijaya became a center of not only political and military power but also Islamic religious authority. Alongside organizing Islamic rituals in mosques (Magik / Masjid), Chế Mân preserved Hindu traditions through temple and tower constructions such as Po Krung Garai, Yang Mum, and Yang Prong. This combination reflected a strategy of religious accommodation, protecting traditional symbols of power while allowing Islam to take root steadily and durably within the court and community. Royal ceremonies, pilgrimages, and international marriages were all integrated with Islam, confirming that the religion had become a tool for consolidating authority and coordinating Champa’s diplomatic relations with regional princes and merchants across the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Figure 9. King Che Man (R'cam Mal, Che Man, Che Man Harijit; Islamic title: Raja Kembayat; Hindu-influenced title: Jaya Simhavarman III), who reigned from 1285 to 1307, was one of the Champa kings (Raja-di-raja). He was a ruler who followed Islam and belonged to the Raday (Rhade, Jarai) ethnic group. He was the son of King Indravarman V and Queen Gaurendraksmi. The consorts of Che Man included: Bhaskaradevi (an Islamic princess from Java), Tapasi (an Islamic princess from Java or Malay), and Trần Huyền Trân (a princess of Đại Việt), daughter of King Trần Nhân Tông. During his nine-month visit and stay in Champa, King Trần Nhân Tông promised to give Princess Huyền Trân in marriage to King Che Man. Photo: Putra Podam.

In the second half of the 14th century, the process of Islamization of the Cham royal family continued as the state religion under Chế Bồng Nga (Sultan Zainal Abidin, reign 1360-1390). Born in Vijaya-Champa as the son of Jaya Ananda (Chế Anan), Chế Bồng Nga inherited the model of centralized power and the multi-layered religious policies of previous Muslim kings. With the title Sultan Zainal Abidin, meaning “The Pious King,” Chế Bồng Nga both consolidated royal authority and expanded the influence of Islam in Champa. He reformed the military, unified the highland chieftains (Rhade, Jarai, Bahnar, etc.), and led several military campaigns to reclaim territories previously lost to Đại Việt. Under Chế Bồng Nga’s reign, Vijaya returned to a period of prosperity and strength, regarded as one of the greatest dynasties of Champa. Royal marriages, particularly with the Muslim princess Siti Zubaidah from Kelantan, continued to strengthen religious and political alliances and expanded relationships with other Islamic kingdoms in the region.

Figure 10. King Chế Bồng Nga (Che Bunga, R'cam Bunga; Islamic title: Sultan Zainal Abidin), belonging to the Jarai ethnic group and practicing Islam, was a king renowned for his northern military campaigns against Đại Việt. He reigned from 1360 to 1390 and established Islam as the state religion of Champa in the 14th century. He is recognized as the most powerful king in Champa’s history, holding absolute authority in the court while also serving as a patron of religious and royal architectural works. Photo: Putra Podam

Research shows that from Po Aluah, Po Krung Garai, Chế Mân to Chế Bồng Nga, there was a systematic process of Islamization, manifested through: (1) the royal family’s adoption and practice of Islam at the centers of power; (2) the organization of both Islamic and traditional Hindu rituals; (3) the use of royal marriages and diplomacy as instruments to consolidate authority; and (4) the expansion of Islamic influence across regional trade and diplomatic networks. This process both preserved Champa’s cultural identity and adapted to Southeast Asia’s political and commercial fluctuations, laying the foundation for the long-term development of the Muslim Cham community in Panduranga during the 14th-15th centuries. This trajectory reflects Champa’s ability to create a multi-religious, multi-ethnic model of kingship that was both flexible and resolute in protecting sovereignty, maintaining internal stability, and asserting its position internationally.

Moreover, the Islamization process was closely linked to military campaigns, administrative policies, and diplomacy. Po Aluah established Vijaya as a power center, creating stability amid threats from Đại Cồ Việt and neighboring forces. Po Krung Garai strengthened relations with Muslim merchants, extending influence to the islands of the Indian Ocean and the Melayu world. Chế Mân continued this tradition, defending territorial integrity against foreign invasions while using Islam to reinforce alliances with neighboring Islamic polities. Chế Bồng Nga not only developed the economy and consolidated central authority but also transformed Vijaya into a military, religious, and commercial hub, enhancing internal strength and diplomatic leverage.

The parallelism and interaction between Islam and Hinduism within the Champa royal family created a multi-layered model of kingship that both preserved tradition and adapted flexibly to political and social changes. This structure ensured internal stability, strengthened diplomatic and commercial cooperation, and fostered a distinctive cultural and religious identity, where Islam coexisted and interacted with Hinduism and indigenous beliefs in both the court and broader society.

The royal Islamization of Champa from Po Aluah to Chế Bồng Nga was thus not merely the adoption of a new religion, but a sophisticated political, cultural, and diplomatic strategy, reflecting Champa’s capacity to harmonize and adapt to regional dynamics. The development of Islam in the Champa court laid the groundwork for the Muslim Cham community in Panduranga while reinforcing the continuity and resilience of royal authority over several centuries.

5.2. Po Rome - The Muslim King of Panduranga

According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), Po Rome ascended the throne in the Year of the Rabbit and ruled for 24-25 years as the son-in-law of Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha). Po Rome’s status as a Muslim king indicates the continuation of Islamic faith within the Panduranga-Champa royal lineage. The Kelantan genealogy confirms that Po Rome was known as Nik Mustafa bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah, placing him within the Islamic royal framework of the Nik and Wan lineages, which held both religious and political authority in Kelantan. His adoption of Islam was not merely a personal choice but a political strategy to strengthen alliances with Islamic centers in the Malay Peninsula, Patani, and Singgora, while expanding Champa’s influence in the volatile 17th-century Southeast Asian context. Research by Pierre-Yves Manguin indicates that Champa kings of this period often used religion as a tool to legitimize power and reinforce the hierarchical order of the court.

Figure 11. Po Klong Mah Nai (reigned 1622-1627), an Islamic (Islam) king who was highly devout in Islam, regnal name: Po Mah Taha. According to the Champa chronicle Sakkarai dak rai patao, he ascended the throne in the Year of the Dog, abdicated in the Year of the Rabbit, ruling for six years, with the capital at Bal Canar (Panrik -Panduranga). The temple of King Po Klong Mah Nai was built on a sandhill near Palei Pabah Rabaong (Mai Lãnh village, Phan Thanh commune), bordering Lương Bình village, Lương Sơn commune, about 15 km from the Bac Binh district headquarters and around 50 km from Phan Thiet city. According to H. Parmentier (Monuments chams de l'Annam, Publ. EFEO, Paris, vol. 1, 1909, p. 38), Po Klong Mah Nai is the name of King Po Mah Taha, who was the father-in-law of King Po Rome (1627-1651). The temple of Po Klong Mah Nai is a site venerating King Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and another consort whose identity was unknown to the Cham people at that time. Photo: Putra Podam.

5.3. Islamization of Panduranga: From Po Mah Taha to Po Rome

Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Klong M’hnai, Po Klong Menai, Po Mah Taha), whose Islamic name was Po Maha Taha, ruled Panduranga from 1622 to 1627. He was born in Panduranga, belonging to the Churu-Raglai ethnic group, and passed away at Bal Canar, Panduranga (present-day Phan Rí Cửa Town, Tuy Phong District, Bình Thuận Province). Po Klong Mah Nai had no direct familial connection with the Po Klong Halau dynasty but had served as a high-ranking official under Po Aih Khang. He was granted the Islamic title Maha Taha and was a devout Muslim. During his six-year reign, based at Bal Canar, he diligently maintained Islam in the royal court while simultaneously preserving the traditional rituals of the Cham Ahier community, thus laying a solid religious and political foundation for his successor. Having no sons, Po Mah Taha married his daughter Than Chan and passed the throne to a talented Churu noble, Po Rome.

Po Rome continued the Islamization policies of his predecessor, strengthening Islam in Panduranga through connections with Muslim clerics from Kelantan and Patani. At the same time, he preserved traditional rituals within the Cham Ahier community, establishing a dual model of coexistence between Awal and Ahier, in which Islam and local rituals coexisted, worshipping the Supreme Being, Allah. Research by Abdul Rahman Tang Abdullah emphasizes that Po Rome once resided in Serembi Makkah (Kelantan), a fact that not only enhanced his personal religious prestige but also reinforced strategic relations with Southeast Asian Islamic centers. This enabled Champa to effectively participate in transregional Islamic trade networks, while Islam became a central element of the kingdom’s political, diplomatic, and cultural policy.

Through the legacy of Po Mah Taha and the religious and diplomatic policies of Po Rome, Panduranga-Champa experienced a profound phase of Islamization, in which Islam not only consolidated royal authority but also regulated the relationship between indigenous beliefs and the regional Islamic network, creating a distinctive political and religious model for Panduranga in the early 17th century.

Figure 12. King Po Rome (Che Rome, Nik Mustafa, Sultan Abdul Hamid Shah, Nik Mustafa Bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah). Po Rome (reigned 1627-1651) was a king of Panduranga-Champa who practiced Islam, succeeding the dynasty of Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), also a powerful Islamic Champa ruler. During his time in Makkah, referred to by the Malay as Serembi Makkah, i.e., the Kelantan principality (Malaysia). Po Rome married an Islamic princess, Puteri Siti (Princess Siti), officially becoming a recognized member of the Islamic royal lineage in Malaysia. Malaysian chronicles record that today’s ruling family of the Kelantan principality descends from King Po Rome. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 13. Map of Đại Việt in 1611, during the period of King Po Rome (Che Rome, Nik Mustafa, Sultan Abdul Hamid Shah, Nik Mustafa Bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah). Po Rome (reigned: 1627-1651). The map of Panduranga during this period included Kauthara (Khánh Hòa), Ninh Thuận, Bình Thuận, Đồng Nai, and part of Lâm Đồng. Source: Đại Việt (territory of Vietnam).

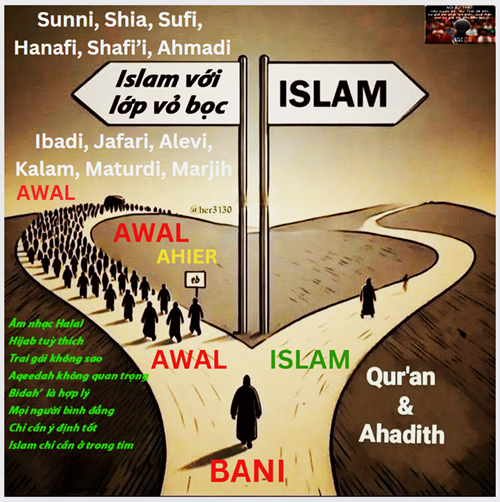

5.4. The Awal-Ahier Religious Sect

A notable feature of Po Rome’s reign was his religious policy. The royal court simultaneously encouraged Muslim followers to observe Islamic rituals while preserving the traditional rites of the Cham Ahier community. This dual practice is exemplified by the construction of Po Rome’s temples and towers to enshrine the Mukha Linga, which served both as a symbol of the deified king according to Hindu beliefs and as a sacred presence in the spiritual life of the Cham. Po Dharma emphasizes that the Awal (early Islam) and Ahier (later Islam) model, which jointly worship Po Allah, functioned not only as a political tool to balance factions within the court but also as a means of fostering cohesion and unity within the Panduranga community during a complex period.

Malaysian and Patani sources also confirm that Po Rome acted as a link between the two religious streams: he was both a member of the Islamic royal lineage of Nik and a king of Champa, responsible for organizing rituals related to traditional Cham practices while maintaining relations with Islamic clerics in Patani and Singgora. This duality illustrates his ability to harmonize political and religious authority, making Po Rome a symbol of sacred and legitimate power in the eyes of both Awal, Ahier communities, and Muslim followers.

According to Cham and Malay chronicles, King Po Rome was a Muslim ruler, well-versed in the Quran and Islamic teachings. The Cham Muslims of that period, while identifying as Bani (followers of the faith), continued to practice matrilineal and matriarchal social structures, which were contrary to traditional Islamic customs. This reflects the fact that Cham and Malay communities adopted Islam from the Arab world but not Arab culture itself. After the 17th century, due to increasing religious conflicts within Cham society, Po Rome’s reign institutionalized religion into two sects with the terms Awal and Ahier, defined as follows:

Awal (ꨀꨥꩊ): The term Awal (derived from Arabic) means “first, prior, original,” referring to Muslims (Cham Hindus or Cham Jat who had converted to Islam centuries earlier) up to Po Rome’s reign, recognizing Po Allah (Aluah) as the Supreme and Only God while still influenced by indigenous Cham elements. This parallels developments in Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries.

In E. Aymonier’s 1906 dictionary, Awal has several meanings:

1. “First, prior.” Example: "meng awal": from the beginning.

2. “Islam.” Example: "gah Awal ": among Islam.

3. “Islamic.” Example: "Cam Awal": Cham Muslims.

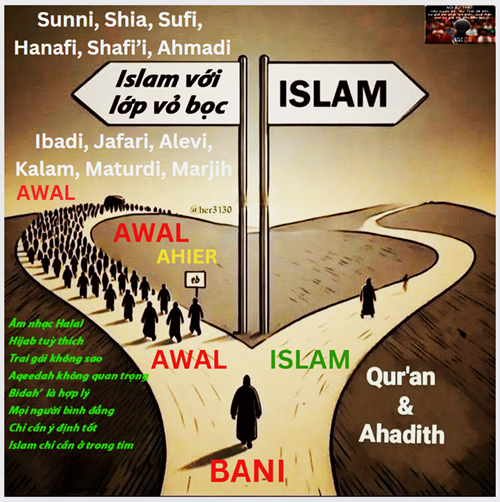

Due to historical factors in Panduranga-Champa, the Awal faith did not strictly adhere to the Quran to eliminate local spiritual or superstitious elements, unlike other Southeast Asian Muslim states. Over time, other Islamic traditions gradually refined their practices according to the Quran to form modern Islam. In contrast, Awal in Panduranga retained its original elements. Today, Awal among the Cham can be considered one branch of Islam alongside Sunni Islam (Arab), Shia Islam (Iran), Ahmadiyya (Pakistan), Kharijite Islam (Oman), Sufi Islam (Libya, Sudan), Wahhabi Islam, and others.

Awal Islam in Panduranga is divided into two classes:

1. Clerics (Acar - ꨀꨌꩉ): Directly worship Allah, the Supreme and Only God, following Muhammad as the final Prophet. Their duties include studying the Quran, observing fasting, performing rituals during Ramadan (Ramawan), Eid al-Adha (Waha), and conducting life-cycle ceremonies of Cham Bani followers.

2. Laypeople (Gahéh - ꨈꨨꨯꨮꩍ): Serve and obey the clerics (Acar) and indirectly worship Allah. If equipped with sufficient knowledge of the Quran, laypeople can become clerics (Acar) and worship Allah directly.

Therefore, discussions of the Awal sect (Early or Panduranga Islam) primarily concern the clerics (Acar) and their ritual system, not the lay followers (Gahéh).

Ahier (ꨀꨨꨳꨯꨮꩉ): The term Ahier or Akhir (from Arabic) means “later, subsequent,” referring to Cham who formerly followed Hinduism, worshipping the Trimurti (Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva), but converted to worship Po Allah under Po Rome due to religious and geopolitical circumstances in Champa and Southeast Asia. In the Ahier community, Po Allah is recognized as the Supreme God, but the Cham Ahier also maintain temples and local cultural practices in Panduranga. According to Po Dharma, Po Aluah in the Ahier community was not the Only God but the Supreme Deity at the head of the pantheon of gods and kings in Panduranga-Champa.

Thus, the term Awal does not alter the intrinsic value of Islam but emphasizes that the Cham had followed Islam and worshipped Allah before Po Rome’s reign. In contrast, Ahier represents a transformation from Hindu Cham to Islamic worship, institutionalized under Po Rome. In this way, Islam reached its peak development, and the Panduranga royal court aimed to guide former Hindu Cham into the Ahier sect to eventually harmonize with the Awal Cham and resolve religious conflicts.

It is important to note that the creation of the Awal and Ahier sects was a product of Po Rome’s reign, not Po Rome himself; there is no evidence that he personally created these two sects. The Awal system, with its two classes (clerics [Acar] worshipping Allah directly and lay Awal [Gahéh] serving the clerics), represents the Panduranga form of Islam and the ritual framework of the Awal sect.

Figure 14. The sects and branches of Islamic followers under the framework of Islam. Photo: Source Islam.

Figure 15. Awal (Agama Awal): Early Islam, Primitive Islam, Awal Islam, or Cham Islam. Awal is one of the 73 branches of Islam worldwide. Photo: Source Islam.

5.5. Two Funeral Rites: Islam and Ahier

The life and career of Po Rome is a story at once tragic, heroic, and majestic. Regardless, Po Rome was a king devoted wholeheartedly to his people and his country, especially revered by the Panduranga-Champa subjects after his death in battle. However, the circumstances of Po Rome’s death remain inconsistently recorded. According to oral tradition, he was captured during a battle, confined in a cage, starved and left thirsty while being transported to Huế, and ultimately took his own life. Dohamide-Dorohiem, E. Aymonier, and other sources record that Po Rome lost the battle and was imprisoned in an iron cage.

The first rite, following Po Rome’s death, was organized by the Panduranga-Champa royal court in the royal mosque (Magik/Masjid), in accordance with the Islamic rites of the Panduranga-Champa monarchy.

Subsequently, Po Rome was also honored with another rite, cremation according to the local Ahier custom for a devout king worshipping Allah. Simultaneously, Cham Ahier followers carved a statue of Po Rome in the form of a Mukha Linga (representing Shiva) to be enshrined in a tower, which had previously been constructed to honor Shiva in the Hindu tradition.

According to G. Moussay and Po Dharma, a report written in Portuguese by a missionary who came to Vietnam claimed that Po Rome was captured and brought to Phú Xuân. Logically, if the Huế court executed him, his body would not have been available for Islamic rites in the mosque or cremation according to Ahier custom. It is possible that Cham subjects performed the rituals symbolically, without the presence of the physical body.

According to Cham tradition, during the cremation rites for Po Rome, Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih) refused to take part because she was a follower of Islam (the Queen accepted only burial and would not undergo cremation). Later, Cham Ahier devotees built a small shrine behind the Po Rome tower to venerate her. In contrast, the Secondary Queen Than Chan (H'bia Than Can) agreed to follow her husband in the cremation ritual, so the Cham Ahier placed the statue of the Secondary Queen Bia Than Can inside the tower beside King Po Rome.

"Note: Because King Po Rome’s body was not present, the Champa royal family performed only the ceremonial rites for him in the mosque (Magik) according to Islamic practice. Afterwards, Cham Ahier devotees also carried out certain procedures following cremation rituals for King Po Rome, but without his physical remains. Therefore, the act of the Secondary Queen Bia Than Chan (H'bia Than Can) ascending the cremation pyre was purely ritual, and she herself was not cremated. Later, Secondary Queen Bia Than Chan went to live in the highlands (present-day Central Highlands) and passed away in 1654, three years after King Po Rome’s death in 1651."

On July 2, 2010, an archaeological team from the Southern Sustainable Development Center conducted an excavation. During the process, they uncovered numerous valuable historical and artistic artifacts, including a ceramic jar from the ruins of the Fire Tower, multiple stone slabs with carved patterns, and more. Notably, the team discovered a tomb beneath the area containing human skeletal remains in the vicinity of Po Rome’s tower. Preliminary assessment suggests this was a “Gahul” or “Makam” Muslim burial site, as some sources on Po Rome’s legend mention the phrase: “Bia Sumut tok Cam di Kut”. Based on this expression, the Cham interpret Bia Sumut as a princess of Islamic origin.

Figure 16. The Po Rome tower area, which contains a “Kabur” or "Makam" tomb of a Muslim (Islamic) individual. It is believed to be the tomb of Queen Bia Sumut, who was of Islamic origin, as some records on Po Rome mention the phrase: "Bia Sumut tok Cam di Kut." Based on this saying, the Cham consider Bia Sumut to have been a princess of Islamic origin. Photo: Putra Podam.

The Islamic burial site discovered next to the temple tower and its relationship with King Po Rome (Nik Mustafa) remains a major unresolved question. It is possible that this was the tomb of Queen Bia Sumut, who had Islamic origins. Nevertheless, this remains an open question for scholars both within Vietnam and internationally, who continue to research in order to provide a definitive answer.

A synthesis of historical evidence indicates that Po Rome’s reign represents the peak period in the integration of political and religious power in Panduranga. During this period, Po Rome not only consolidated royal authority but also connected Panduranga to the broader network of Southeast Asian Islamic religious centers, while simultaneously preserving indigenous Cham spiritual traditions. His policy of parallel religious practices and royal deification rituals not only safeguarded Cham cultural identity but also created the image of a king who was both close to his people and imbued with sacred authority, extending the cultural influence and political power of Panduranga across a wider region, from Kelantan to Patani and Singgora.

Figure 17. King Po Rome, regnal name: Nik Mustafa Bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah. He belonged to a royal lineage of Islam in Serembi Makkah, within the principality of Kelantan-Malaysia. The image above shows King Po Rome with the Po Rome Tower. Photo: Putra Podam.

5.6. Misconceptions about Po Rome’s Religious Reconciliation Policy

In the history of scholarship on King Po Rome, some earlier studies have characterized him as a syncretist of religion and politics, suggesting that he blended indigenous Cham belief systems with Islam to create a model of religious assimilation. However, this assessment lacks practical and scholarly grounding, reflecting limited understanding of Cham culture, religion, and ritual structures.

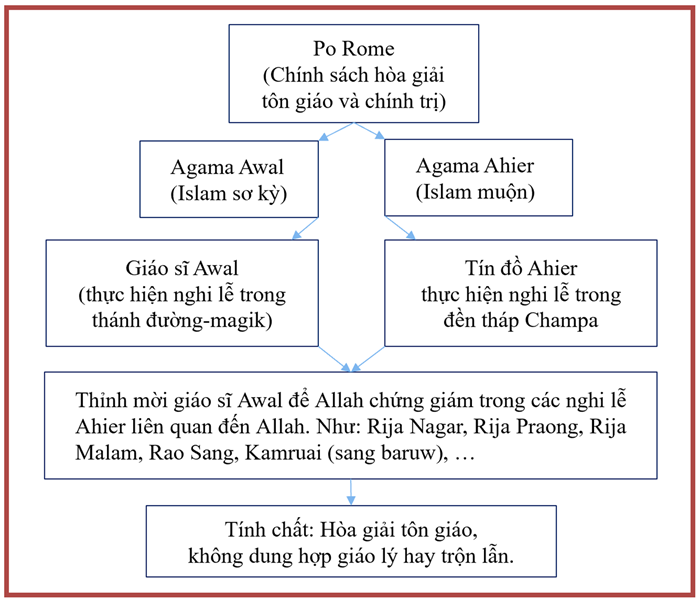

A primary cause of these misconceptions is the failure to clearly distinguish between the two Cham Islamic traditions: Agama Awal (early Islam) and Agama Ahier (later Islam). Agama Awal, or early Islam, still retained indigenous influences but maintained the core principles of Islam: exclusive worship of Allah, ritual practice in mosques (magik), and a strict avoidance of participation in Ahier temples, towers, or indigenous Cham rituals. Awal clergy (Acar) never performed rituals for Hindu deities or Cham-deified gods. Inviting an Awal Acar to officiate in Ahier rituals served only to confirm Allah as witness, not to engage in deity worship.

Conversely, Agama Ahier had no clerics specifically devoted to Allah. Therefore, in rituals involving Allah-such as Rija Nagar, Rija Praong, Rija Malam, Rija Sua, Mbeng Bar Huak, Rao Sang, Kamruai (sang baruw), etc.-Ahier devotees often invited Awal clerics to perform portions related to Allah, including recitations of Surah Al-Fatihah, Ash-Shams, and various Du’a. This arrangement functioned as a practical, socially and religiously pragmatic support mechanism, not as doctrinal blending. The assertion that Po Rome “fused” the two religions, with Awal officiating Ahier rites and vice versa, is a fundamental misinterpretation.

The Rija ritual exemplifies this misunderstanding. Originating from the Malay royal tradition (Mak Yong), influenced by local culture and later spread within the Malay Muslim community, Rija carries profound humanistic significance. It reinforces Cham connection to ancestral roots, consolidates cultural and moral values, and fosters personal development within the community. The presence of Awal Acar clergy in the ritual ensures that Allah witnesses the proceedings; it is not connected to Cham or Hindu deities. After its ban by Malaysia’s PAS party in 1990, the Rija (Mak Yong) ritual survives only as a stage performance, recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Misconceptions about Po Rome stem from reliance on unverified oral accounts, failure to distinguish between religion and belief systems, and conflation of faith with cultural practice. These errors were subsequently repeated in domestic scholarship, perpetuating a flawed view of Po Rome’s religious role. A rigorous historical and religious studies approach demonstrates that Po Rome was not a syncretist, but rather a practitioner of religious and political reconciliation: respecting the functional boundaries of each tradition while ensuring social stability and preserving Panduranga’s cultural identity.

Figure 18. Diagram explanation: Po Rome stands at the center as the policymaker, coordinating religious relations, not blending doctrines, but ensuring religious legitimacy within the multi-religious community of Panduranga.

Agama Awal: Awal clerics perform Islamic rituals in the mosque only, without participating in Ahier ceremonies or Hindu worship.

Agama Ahier: There is no dedicated official for Allah; Ahier followers invite the Awal Acar to witness Allah during important rituals such as Rija. The relationship between the two systems represents ritual reconciliation, reflecting flexible religious practice and Po Rome’s multi-religious governance policy, rather than doctrinal syncretism.

Rija ritual: The participation of the Awal Acar pertains only to Allah and is unrelated to Champa or Hindu deities, accurately reflecting ritual function and the essence of religious reconciliation. Photo: Putra Podam.

5.7. Misconceptions about the Term “Bani”

The term “Bani” is often misunderstood as the name of an independent religion within the Cham community. In reality, it is a socio-religious designation referring to followers of Allah within the Agama Awal system. This misconception has affected historical and religious research, as well as producing legal and social consequences in modern life. This section will analyze the origin, meaning, and localization process of the term Bani, clarify misunderstandings regarding the so-called “Bani religion,” and examine its impact on the Cham Awal community.

5.7.1. Origin, Semantics of “Bani,” and Localization in Southeast Asian Islamic Traditions

The term “Bani - ꨝꨗꨪ ” exemplifies semantic adaptation and cultural accommodation in the transmission of Islam from the Arab world to Southeast Asia. Originally, “Bani” comes from the Arabic Banī (بني), the iḍāfah form of ibn/banū, meaning “descendants,” “children,” or “members of a lineage or community.” In the Qur’an and Hadith traditions, the term appears in phrases such as Banī Isrā’īl, Banī Hāshim, or Banī Quraysh, to indicate genealogy or social groups, and is never used as the name of an independent religion.

When Islam spread to the Malay world, Java, and Champa from the 10th century onward, Arabic terms, including “Bani,” underwent semantic shifts in regional usage, referring to indigenous Muslim communities or converts. Classical dictionaries by Aymonier and Cabaton (1906) explain that “Bani” literally means “children” in Arabic, but in the Southeast Asian context, it came to signify “Muslim” or “follower of Islam.” R.P. Durand (1903) also notes that “Bani” is a transliteration of “Beni,” meaning “children,” and is linked to Islam in local communities.

In the Champa context, Bani is associated with the process of localized Islamization, forming the Agama Awal system from the 17th century. Agama Awal is an indigenous form of Islam, combining a clerical class (Acar) with Koran-based rituals, while maintaining devotion to Allah and reverence for the Prophet Muhammad. Islamic essence is preserved through rituals such as Khatan, Shahādah recitation, and the practices of Acar clergy. In this system, Bani is never the name of a religion; rather, it is a socio-religious designation for individuals or communities who worship Allah. Cham people do not refer to “Agama Bani”; the term appears only in phrases such as Anak Bani, Cham Bani, or Bani Cham. The ritual “Khatan tama Bani” is an initiation into Islam, not a conversion into a religion called Bani.

From an academic perspective, it is clear that Bani is a socio-religious term reflecting the status of a believer and affiliation with Allah within the Cham Awal tradition. Misunderstanding Bani as an independent religion distorts historical and religious research and the community’s perception. The term demonstrates cultural adaptation, the localization of Islam, and how Southeast Asia integrated Arabic nomenclature, while maintaining continuity in Cham religious tradition for over a millennium.

5.7.2. Misconceptions about the “Bani Religion” and Legal-Social Consequences in the Cham Awal Community

In recent decades, some have claimed that the Cham Awal community follows a religion called “Bani,” and suggested that the Vietnamese state should recognize “Bani religion.” This view lacks scientific, historical, and legal basis and contradicts the Agama Awal system, which is localized Islam from the 17th century. The misunderstanding originated from administrative practices in Bình Thuận and Ninh Thuận provinces, where some local authorities recorded “Bani” as the religion on citizens’ ID cards, even though the official state registry only lists “Islam.” This led some to believe that the state recognized a religion named Bani, creating social misperceptions and unsupported demands.

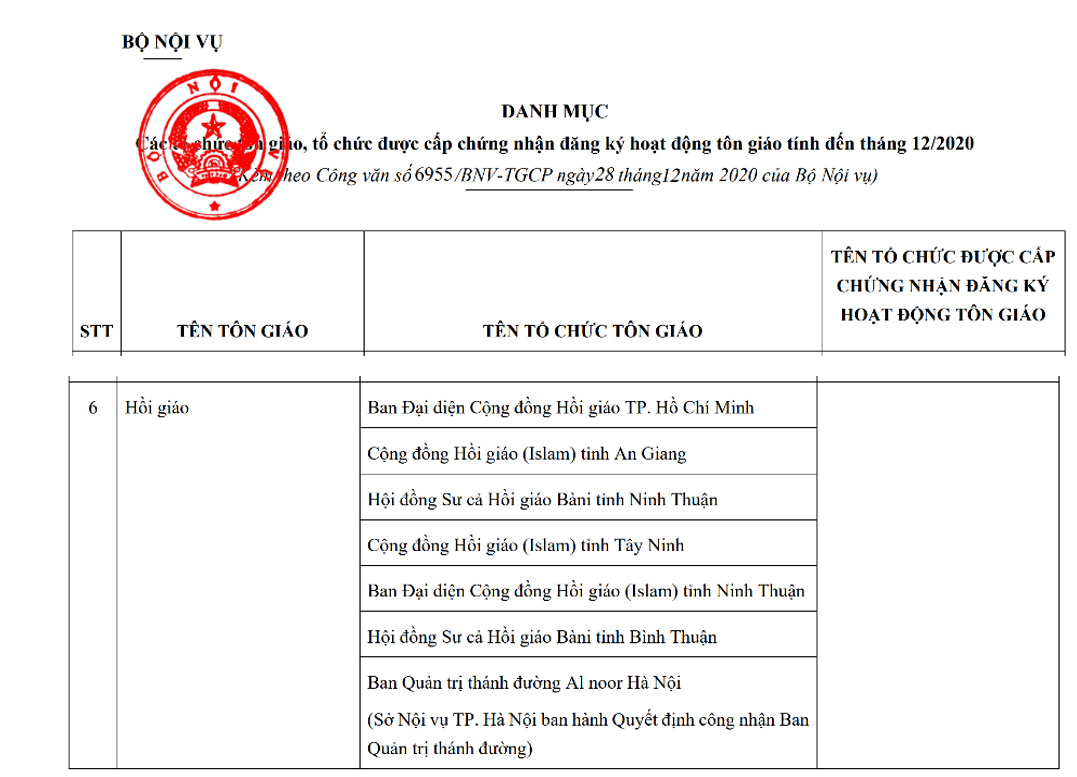

"According to Official Dispatch No. 6955/BNV-TGCP dated December 28, 2020, issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Vietnam has 36 religious organizations belonging to 16 recognized religions. Item number (6) is Islam, which includes 7 religious organizations."

Figure 19. According to Official Dispatch No. 6955/BNV-TGCP dated December 28, 2020, issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs, item number (6) is Islam, which includes 7 religious organizations.

Reference: List of Religions and Religious Organizations in Vietnam

When issuing identity cards, the Public Security Departments of Ninh Thuận and Bình Thuận Provinces did not rely on the official list of religions provided by the Government Committee for Religious Affairs of Vietnam. Instead, they issued identity cards based solely on the applicant’s declaration, arbitrarily recording the religion as 'Bani', which has led to the consequences seen today.

Academically, this confusion has serious consequences. No religion named Bani exists worldwide; it is merely a socio-religious designation for Cham Awal Muslims within localized Islam. Referring to Bani as an independent religion misrepresents its nature, disrupts the historical continuity of Cham religious practices, and risks fragmenting community identity. Legally, any claim for recognition of “Bani religion” has no basis, as Bani has no distinct doctrines, scriptures, or organizational structure. This misconception also complicates religious policy planning and scholarly research by misrepresenting the Agama Awal system and the Cham Awal community.

To ensure accuracy in historical and religious research and correct community understanding, it must be affirmed that Bani is solely a designation for Islam adherents, reflecting status and community, not a religion. Proper understanding of Bani helps preserve Cham Awal religious identity and maintain historical continuity with Champa’s Islamization process, ensuring consistency in research, policy, and education regarding the Cham Awal community.

5.7.3. Academic Conclusion on the Term “Bani”

Based on research into its origin, semantics, and localization, Bani is not the name of an independent religion but a socio-religious term describing the status of Islam adherents within the Cham Awal community. Misunderstandings about the “Bani religion” primarily arise from administrative errors, leading to distorted perceptions, but do not reflect the historical or religious reality of the community. Correctly situating Bani within the Agama Awal system preserves the continuity of localized Islam, reinforces academic understanding, and informs accurate religious policy.

Figure 20. Bani, Muslim, and Islam, the branches and sub-branches of Islamic followers under the framework of Islam. Photo: Source Islam.

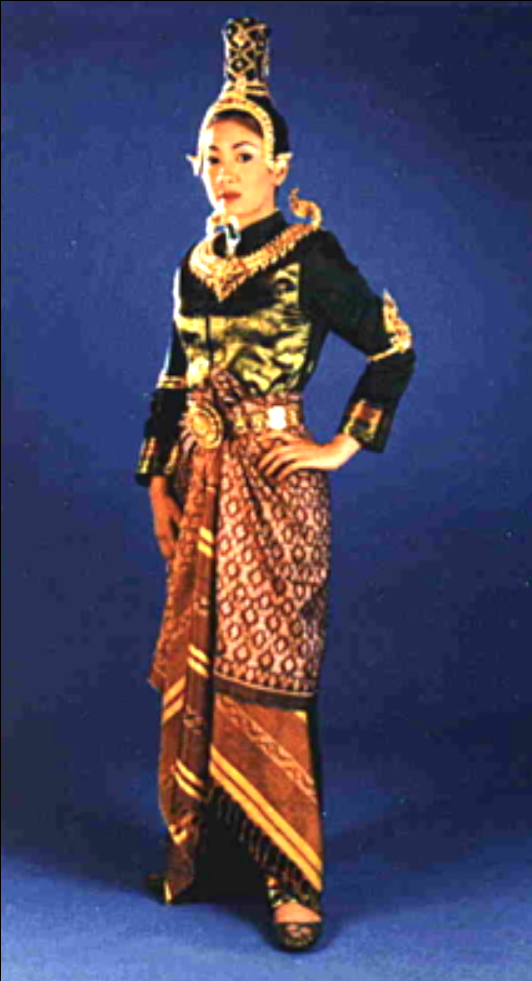

6. Queen Bia Sucih and Bia Than Can

During Po Rome’s reign, the queens were not only the king’s consorts but also central figures in politics, religion, and cultural symbolism. The two principal queens, Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih or H’bia Than Cih) and Secondary Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can), reflect two contrasting religious orientations within the Panduranga-Champa court, while also illustrating the significant status of royal women in 17th-century Panduranga society. Research by Po Dharma emphasizes that the role of queens in Panduranga-Champa extended beyond political marriage to include religious authority and the symbolic representation of royal power. Pierre-Yves Manguin and Abdul Rahman Tang Abdullah also confirm that queens acted as intermediaries between the king, the court, and religious communities, particularly in maintaining harmony among diverse religious systems.

6.1. Origins and Political-Religious Role

Bia Sucih, daughter of King Po Mah Taha (r. 1622-1627), was Po Rome’s principal queen. According to the Kelantan genealogy, she was a devout Muslim and held significant political authority within the court. Her presence strengthened alliances with regional Islamic centers, including Kelantan, Patani, and Singgora, while ensuring the influence of Islam within Champa’s internal affairs. In contrast, H’bia Than Can was of the Rhade ethnic group (Princess Hadrah Hajan Kapak), from the Vijaya Degar royal lineage, and her role was to preserve indigenous folk rituals.

6.2. Queen Sucih: Symbol of Devout Islam

Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih - ꨝꨳ ꨧꨭꨌꨪꩍ) is regarded as the embodiment of Islam during Po Rome’s reign. According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao) and the Kelantan genealogy, when the Ahier community performed the cremation rituals for Po Rome, Queen Sucih refused cremation because she was a Muslim (accepting only burial in accordance with Islamic law). Subsequently, the Cham Ahier community built a small shrine behind the Po Rome tower to venerate Queen Sucih.

Abdul Rahman Tang Abdullah emphasizes that this Islamic ritual practice was not merely a personal choice but also a strategic measure to reinforce Islamic authority within the court, demonstrating the royal family’s legitimacy in the Southeast Asian Muslim community. Queen Bia Sucih is also recorded participating in religious diplomatic activities, serving as a liaison with clerics from Patani, Kelantan, and Singgora, thereby extending Panduranga-Champa’s influence within the regional Islamic network.

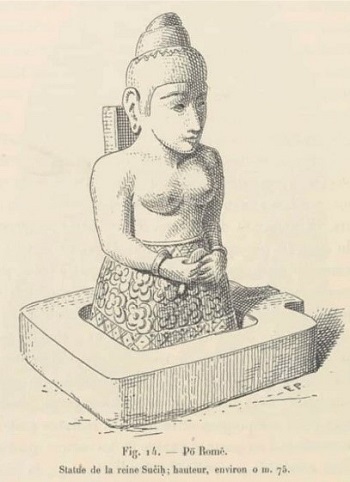

Figure 21. Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih). According to the original version of the first statue model, there was no Thrah (Srah) inscription engraved on her chest. The photograph was taken by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949) in his book titled Inventaire descriptif des monuments Cams de l’Annam (Descriptive Inventory of Cham Monuments in Annam). This statue model was lost when first discovered, then lost a second time in 1993. Photo: Henri Parmentier.

Figure 22. Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih). According to the original version of the first statue model, there was no Thrah (Srah) inscription engraved on her chest. This drawing is by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949) in his book titled Inventaire descriptif des monuments Cams de l’Annam (Descriptive Inventory of Cham Monuments in Annam). This statue model was lost when first discovered, and later lost again in 1993. Image: Henri Parmentier.

After the original statue of Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih) was lost in 1993, the Cham Ahier community recast a new statue for Bia Sucih and inscribed on her chest a line of Thrah (Srah) script. The impression of this inscription is still preserved in France and reads: “This is the story of Bia Sucih, a revered figure in the kingdom. Because she did not follow her husband to the funeral pyre, it is inscribed on Bia Sucih’s chest.”

The Thrah (Srah) inscription engraved on the chest of Bia Sucih (Queen Sucih) is as follows:

ꨗꨫ ꨚꨗꨶꨮꩄ ꨝꨳꨩ ꨧꨭꨌꨪꩍ

ꨣꨩꨕꨮꩍ ꨧꨯꨱꩃ ꨛꨯꨮ ꨚꨤꨬ

ꨘꩆ ꨅꩍ ꨙꨪꩀ

ꨀꨚꨶꨬ ꨧꨯꨱꩃ ꨚꨧꩃ

ꨓꨕꨩ ꨝꨳꨩ ꨧꨭꨌꨪꩍ

The Thrah (Srah) inscription was transliterated into Rumi Cham 2000 (Putra Podam):

"Ni panuec Bia Sucih

Radeh saong Po palei

Nan oh ndik

Apuei saong pasang

Tada Bia Sucih ".

This confirms that the statue of Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih) located behind the Po Rome tower is indeed Bia Sucih. Based on this observation, it can be affirmed that Bia Sucih did not accept cremation (because she was not a Hindu or Ahier follower, but a devout Muslim, the daughter of the Islamic king Po Mah Taha) and therefore only accepted burial according to Islamic (Islam) rites.

Figure 23. Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih), this statue was carved for the second time after the original statue was lost in 1993. On this new statue, Cham Ahier devotees engraved the Thrah (Srah) inscription on Queen Sucih’s chest. The second version of the statue was also lost in 2008. Photo: EFEO France.

Figure 24. Queen Sucih (Bia Sucih), the statue carved for the third time, currently placed in the temple at Po Rome tower. Photo: Putra Podam.

6.3. Secondary Queen Than Chan: Religious Harmony and the Cremation Legend

In contrast, the secondary consort Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can - ꨝꨳ ꨔꩆ ꨌꩆ) followed the cremation ritual according to the indigenous Hindu tradition in Panduranga-Champa. The Cham Ahier community placed her statue in the tower next to King Po Rome, reflecting the continuation of royal deification practices according to Cham beliefs. Po Dharma describes this as evidence of the Cham court’s ability to reconcile religious differences, where Islam and indigenous beliefs coexisted within rituals, culture, and politics. Cham sources emphasize that by participating in the cremation ritual, H’bia Than Can reinforced royal authority and the divine status of the king, while also becoming a symbol of the continuity of indigenous cultural traditions during Po Rome’s reign. The legend of her cremation also reflects how the local Cham Ahier community preserved cultural memory through architecture, sculpture, and ritual worship.

Figure 25. Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can), original statue inside the tower, beside the deity Po Rome. Photo: EFEO France.

Figure 26. Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can), the original first statue, which was stolen. Photo: EFEO France.

Figure 27. Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can), reconstructed statue. Photo:Putra Podam.

Figure 28. Queen Than Chan (H’bia Than Can), second version of the statue, currently inside the tower beside King Po Rome. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 29. Princess H’bia Hadrah Hajan (Hadrah Hajan Kapak), born 1630-1654, of the Rhade ethnic group. H’bia Hadrah Hajan became the secondary consort Bia Than Chan (H’bia Than Can or Bia Than Can: meaning Queen Than Can), and was the daughter of a Rhade (Degar, Ede) chief. In the Rhade language, H’Drah Hajan Kpă means “Rain Seed Princess.” According to tradition, Princess H’bia Hadrah Hajan’s beauty was said to be as pure as distant raindrops, like pristine ice, and stately. Bia Than Chan served as secondary consort from 1645-1651. Some Rhade legends claim that Bia Than Chan did not die immediately at her cremation, but was kept alive, later living on the highlands, and eventually passed away in 1654.

|

Person |

Year of Birth |

Reign |

Year of Death |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Po Rome |

1595 |

1627-1651 |

1651 |

|

Bia Than Can |

1630 |

- |

1654 |

Figure 30. Po Rome was born in 1595, reigned from 1627-1651, and died in 1651. Bia Than Chan (H’bia Than Can) was born 1630-1654 and became the secondary consort from 1645-1651. Some Rhade legends claim that Bia Than Chan did not die immediately at her cremation, but was kept alive, later lived on the highlands, and eventually passed away in 1654.

6.4. Political Marriages

In addition to his two principal consorts, Bia Sucih (Bia Than Cih) and H’bia Than Can, representing the two opposing religious directions in the Panduranga-Champa court, Po Rome also entered into political marriages with several other princesses.

During his time in Makkah-referred to by the Malay as Serembi Makkah, a small kingdom in Kelantan (Malaysia)-Po Rome married Princess Kelantan Puteri Siti (Princess Siti). From that point, Po Rome officially adopted the holy name Nik Mustafa, with the full name Nik Mustafa Bin Wan Abul Muzaffar Waliyullah, formally becoming a recognized member of the royal lineage under Islam in Malaysia. Malaysian chronicles record that the rulers of the Kelantan principality today are descendants of King Po Rome.

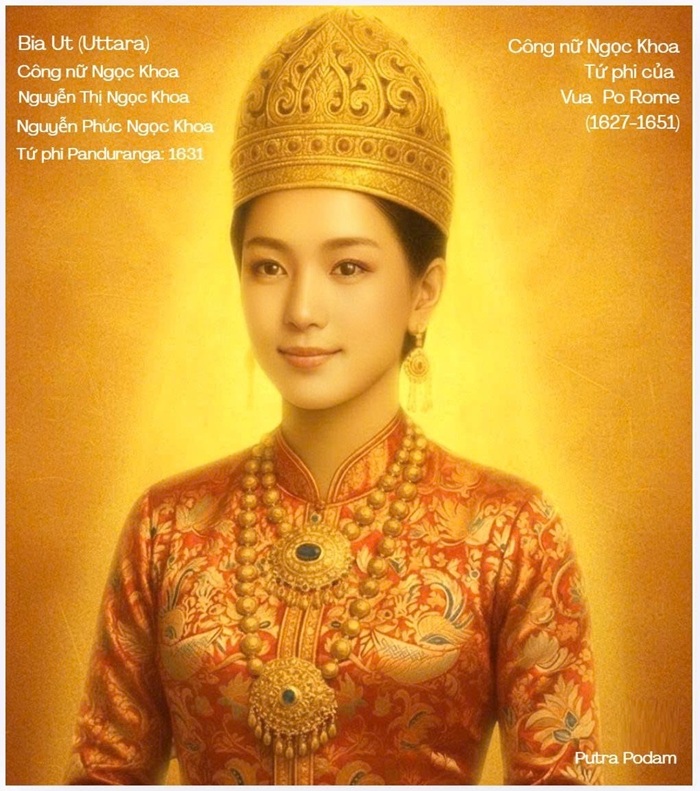

Princess Ngoc Khoa, full name Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Khoa, was the younger full sister of Princess Ngọc Vạn and the third daughter of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên. The Cham people called her Bia Ut (Ut; Mal. Skt. Uttara: “North”), meaning the Northern Princess, or Princess of Đại Việt. According to the Nguyễn Phước clan genealogy, Ngọc Khoa was married to King Po Rome in the year Tân Mùi (1631). This marriage strengthened diplomatic ties between the two states, allowing Lord Nguyễn to concentrate his forces against Lord Trịnh in Đàng Ngoài, while also creating opportunities for the Vietnamese to expand their territory southward.