Name: PhD. Putra Podam (Văn Ngọc Sáng)

Name: PhD. Putra Podam (Văn Ngọc Sáng)

Video: King Po Klong Mah Nai, an Islamic (Muslim) ruler

Po Klong Mah Nai, also known as Po Mah Taha under his Islamic title Maha Taha, was ruler of Panduranga from 1622 to 1627 and a key figure in seventeenth-century Panduranga-Champa history. French scholarly sources often classify him among the Muslim rulers of Champa, indicating the growing importance of Islam in the political and social institutions of the Panduranga court. He was born in Panduranga-Champa and died at Bal Canar (Parik-Panduranga), in the present-day Phan Rí-Bình Thuận area. Of Churu and Raglai origin, Po Mah Taha had no genealogical connection to the Po Klong Halau dynasty (1579-1603) (Aymonier, 1890).

According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), Po Klong Mah Nai ascended the throne in the Year of the Dog, abdicated in the Year of the Rabbit, ruled for six years, and ruled from a capital at Bal Canar. In Nguyen-dynasty Sino-Nom sources, his name appears as Bà Khắc-Lượng Như-Lai, a Sinicized transcription of his Cham title.

Before becoming ruler, Po Klong Mah Nai served as a senior official under Po Aih Khang (1618-1622) and was granted the title Maha Taha, reflecting his prominent administrative and military role. A Muslim ruler, he promoted the influence of Bani (Islamic) elites within the court while maintaining accommodation with Hindu religious communities to preserve social stability. His Islamic name combines the Cham royal title Po with the Arabic-derived Maha Taha, denoting religious and political authority. After his death, he was posthumously honored with the title Sulatan Ya Inra Cahya Basupa (Sultan Jaya Indra), reflecting a synthesis of Islamic, Indianized, and indigenous Champa cultural traditions (Durand, 1906).

Po Mah Taha had one daughter, Bia Than Cih (Bia Sucih), and designated Po Rome (r. 1627-1651), a capable Churu official, as his successor, cementing the succession through marriage. This form of succession emphasized merit and political alliance rather than dynastic lineage and contributed to the increased prominence of highland groups in Panduranga-Champa society.

During his reign, Po Mah Taha strengthened central authority through administrative oversight, taxation, and the protection of maritime trade routes. He expanded diplomatic and commercial relations with neighboring states and Malay Muslim networks, contributing to Panduranga’s economic stability in the South China Sea. His reign represents a significant phase of Islamization in seventeenth-century Panduranga, particularly among the ruling elite, setting the stage for later Cham migrations to Cambodia and Malaysia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries following conflicts with Đại Việt.

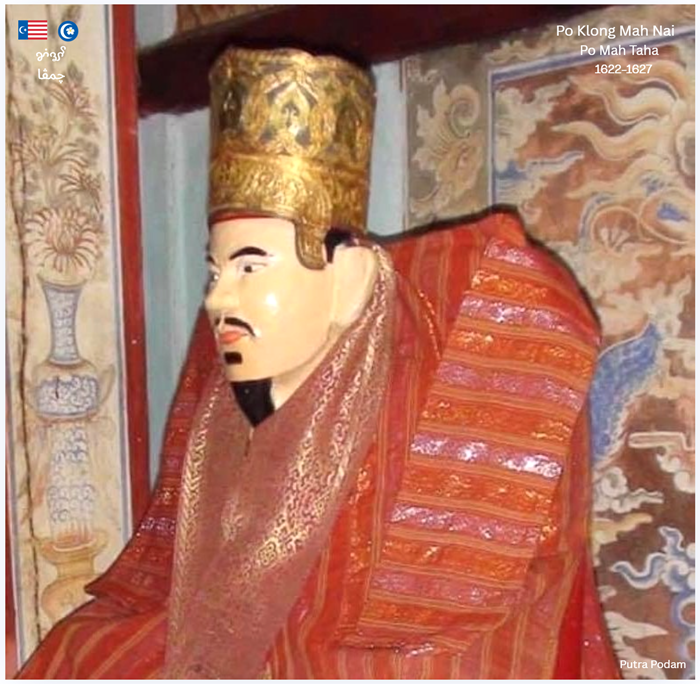

Figure 1. Po Klong Mah Nai (r. 1622-1627), a Muslim king and a devout adherent of Islam, bearing the Islamic title Maha Taha. According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), he ruled for six years with his capital at Bal Canar (Panrik-Panduranga). The temple of Po Klong Mah Nai, built on a sand dune near Palei Pabah Rabaong (Phan Thanh commune, Bắc Bình District), is dedicated to King Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and other Cham royal consorts. According to H. Parmentier (1909), Po Klong Mah Nai was another name for Po Mah Taha, the father-in-law of King Po Rome (1627-1651). Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 2. King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha, Maha Taha), who reigned from 1622 to 1627, was a Muslim ruler. The original statue before it was dressed in Champa royal regalia. Photo: Putra Podam.

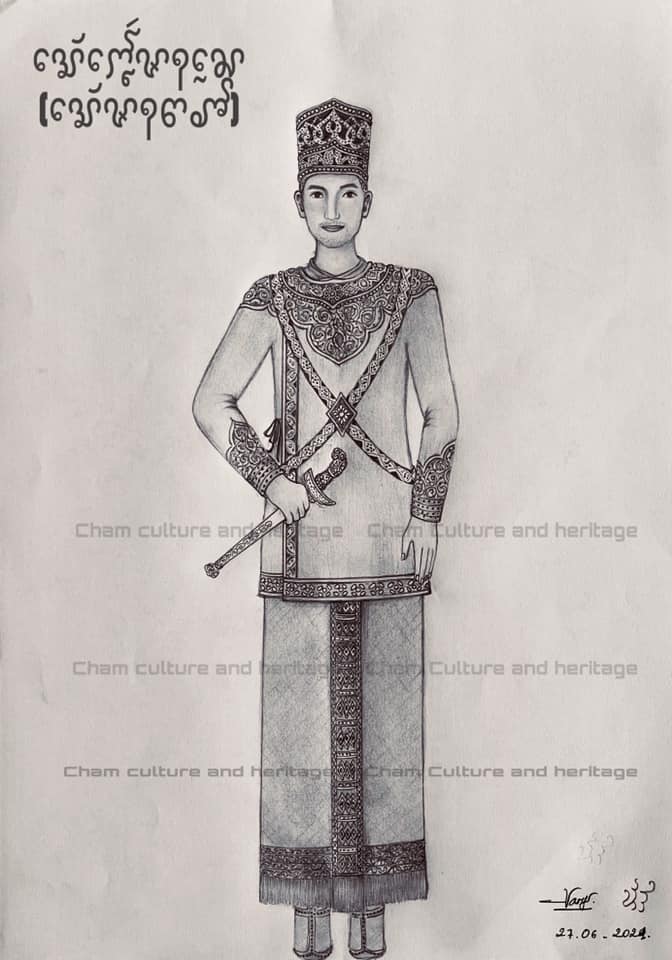

Figure 3. King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha, Maha Taha), who reigned from 1622 to 1627, was a Champa ruler who adhered to Islam. Based on the original statue before it was dressed in Champa royal attire, Putra Podam used AI technology to reconstruct the image and replace the clothing with seventeenth-century Champa royal regalia. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 4. King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha, Maha Taha), who reigned from 1622 to 1627, was a Champa ruler who adhered to Islam. Based on the original statue before it was dressed in Champa royal attire, Putra Podam used AI technology to reconstruct the image and replace the clothing with seventeenth-century Champa royal regalia. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 5. Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), who reigned from 1622 to 1627, was a ruler deeply devoted to Islam. Photo: Collected.

The Po Klong Mah Nai Temple is located on a sand mound in Palei Pabah Rabaong (Mai Lãnh hamlet, Phan Thanh commune), bordering Lương Bình hamlet (Lương Sơn commune), about 15 km from Bắc Bình District center and 50 km north of Phan Thiết City. It is a folk and religious site associated with the worship of Champa kings in Panduranga.

According to Henri Parmentier (Monuments chams de l’Annam, Vol. I, 1909, p. 38), “Po Klong Mah Nai” is the Cham popular name for King Po Mah Taha (r. 1622-1627), the father-in-law of Po Rome (1627-1651). The temple honors Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and another Cham royal consort, reflecting Champa traditions of venerating kings and queens through folk religion.

Folk accounts and French sources report that the temple burned in the late 19th century and was later rebuilt by the local Cham community. In 1964, it underwent major restoration by the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam, which stabilized its current architectural form.

Figure 6. The restoration commemorative plaque at Po Klong Mah Nai Temple, dated 18 December 1964, installed by the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam. Photo: Putra Podam.

On 7 January 1993, the Po Klong Mah Nai Temple was designated a national historical and artistic site by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture and Information under Decision No. 43/VH/QĐ. However, the commemorative plaque placed at the entrance by the Binh Thuan Department of Culture states that Po Klong Mah Nai was the last king of the Champa kingdom. This assertion is entirely inconsistent with Champa historical sources and significantly misrepresents the historical chronology of Panduranga.

According to the Panduranga chronicles, especially the work of Po Dharma (Le Panduranga (Campa) 1802-1835, EFEO, 1987), Po Mah Taha (Po Klong Mah Nai) was the 18th ruler in the dynastic sequence, reigning from 1622 to 1627, and abdicated in favor of Po Rome in 1627. Champa continued to exist for more than two additional centuries, with successive kings ruling until the kingdom was abolished by Emperor Minh Mạng in 1832. The last ruler of Champa, as confirmed in Cham sources, was Po Phaok The (1828-1832), who governed Panduranga during its final period before the 1832-1835 uprising.

Therefore, labeling Po Klong Mah Nai as the “last king of Champa” is a historical error, likely resulting from outdated documentation or a confusion between religious veneration titles and the actual dynastic chronology.

Figure 7. The stele erected at the main gate of Po Klong Mah Nai Temple, which venerates King Po Klong Mah Nai (r. 1622-1627). The content of the stele was prepared under the direction of the Lam Dong Department of Culture, Sports, and Tourism (formerly Bình Thuận Province). However, the historical information on the stele contains several inaccuracies compared to Champa historical sources. Photo: Putra Podam.

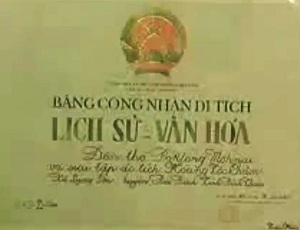

Figure 8. Po Klong Mah Nai Temple was designated a National Historical and Artistic Site of Vietnam under Decision No. 43/VH/QĐ dated 7 January 1993 by the Ministry of Culture and Information. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 9. Po Klong Mah Nai Temple, which venerates King Po Klong Mah Nai (r. 1622-1627), a Muslim ruler of the Champa polity holding the Islamic title Maha Taha. According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), he ascended the throne in the Year of the Dog, abdicated in the Year of the Rabbit, ruled for six years, and established his capital at Bal Canar (Panrik, Panduranga), the political center of Panduranga in the seventeenth century. The temple is built on a sand mound in Lương Bình hamlet, Lương Sơn commune, Bắc Bình District, Bình Thuận Province, approximately 15 km from the district administrative center and 50 km from Phan Thiết City. It serves as a ritual and commemorative space dedicated to King Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and other Cham consorts, preserving the historical memory and religious traditions of the Cham community in southern Champa. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 10. Po Klong Mah Nai Temple, which venerates King Po Klong Mah Nai (r. 1622-1627), a Muslim ruler of the Champa polity holding the Islamic title Maha Taha. According to the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), he ascended the throne in the Year of the Dog, abdicated in the Year of the Rabbit, ruled for six years, and established his capital at Bal Canar (Panrik, Panduranga), the political center of Panduranga in the seventeenth century. The temple is built on a sand mound in Lương Bình hamlet, Lương Sơn commune, Bắc Bình District, Bình Thuận Province, approximately 15 km from the district administrative center and 50 km from Phan Thiết City. It serves as a ritual and commemorative space dedicated to King Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and other Cham consorts, preserving the historical memory and religious traditions of the Cham community in southern Champa. Photo: Putra Podam.

The stone stele records that the north side venerates the Cham queen Bia Som, while the south side venerates a secondary consort identified as a Vietnamese woman, Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Thương. The stele further states: “The southern temple venerates the Vietnamese secondary consort and her two Kut statues”.

According to Putra Podam and the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai Dak Rai Patao), Po Klong Mah Nai was a Muslim king whose principal wife was Queen Bia Som, along with several secondary consorts of Cham origin. There is no historical research, French archival material, or chronicle that records Po Klong Mah Nai marrying a Vietnamese princess.

This misrepresentation affects the understanding of Champa religion and culture. Po Klong Mah Nai was a Muslim ruler, and asserting that he married a Đại Việt princess distorts knowledge of the dynasty’s religious orientation, as well as the political and social relations between Panduranga and neighboring kingdoms. Correcting or removing this claim is necessary to preserve historical authenticity and maintain the value of cultural and educational research.

All ancient Cham sources, including the Panduranga chronicle (Sakkarai dak rai patao), as well as studies by French scholars and Cham researchers of the twentieth century, only record Po Mah Taha’s wife as Queen Bia Som along with several secondary consorts from indigenous Cham lineages. No Cham document, Nguyễn dynasty record, or EFEO report mentions that Po Klong Mah Nai married a Vietnamese woman, nor that he had children with a Vietnamese secondary consort, as claimed on the stele.

According to Henri Parmentier, the first systematic surveyor of Cham towers and temples, the Po Klong Mah Nai Temple venerates Po Mah Taha, Queen Bia Som, and a Cham secondary consort. Similarly, Po Dharma, one of the most important twentieth-century scholars of Champa, in Chroniques des rois de Panduranga and Le Panduranga (Campa) 1802-1835, does not mention the presence of a Vietnamese secondary consort in any seventeenth-century Panduranga reign.

Even the memoirs and ethnographic records of the Cham under French colonial rule (e.g., Moussay, Cabaton), which detail noble marriages extensively, contain no record of a Vietnamese secondary consort of Po Klong Mah Nai.

Therefore, the conclusion regarding a “Vietnamese secondary consort” in the temple is based solely on modern political interpretations and lacks any foundation in Cham or Vietnamese historical sources. Including this information on the monument does not ensure historical accuracy and should be reconsidered and corrected based on the original documentary evidence.

Figure 11. Queen Bia Som (Po Bia Som), the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), a Muslim ruler. The illustration was created by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949), a French scholar and architect, and Director of the Archaeological Service of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in Vietnam. He conducted extensive research, documentation, and surveys of Champa monuments, and his drawings of statues and monuments were published in the renowned work Inventaire descriptif des monuments Cams de l’Annam. Photo: Henri Parmentier. Edited by Putra Podam.

Figure 12. Queen Bia Som (Po Bia Som), the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), a Muslim ruler. The illustration was created by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949), a French scholar and architect, and Director of the Archaeological Service of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in Vietnam. He conducted extensive research, documentation, and surveys of Champa monuments, and his drawings of statues and monuments were published in the renowned work Inventaire descriptif des monuments Cams de l’Annam. Photo: Henri Parmentier. Edited by Putra Podam.

Figure 13. Queen Bia Som (Po Bia Som), the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), was a Muslim queen. The statue was photographed before being dressed in Champa royal attire. It is located in the north chamber of Po Klong Mah Nai Temple. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 14. Queen Bia Som (Po Bia Som), the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), was a Muslim queen. The original photograph was taken by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949), a French scholar and architect, and Director of the Archaeological Service of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in Vietnam. Based on Parmentier’s photograph, Putra Podam used AI technology to recreate the queen’s image in seventeenth-century Champa cultural attire. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 15. Queen Bia Som (Po Bia Som), the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), was a Muslim queen. The original photograph was taken by Henri Parmentier (1871-1949), a French scholar and architect, and Director of the Archaeological Service of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in Vietnam. Based on Parmentier’s photograph, Putra Podam used AI technology to recreate the queen’s image in seventeenth-century Champa cultural attire. Photo: Putra Podam.

The architectural complex of Po Klong Mah Nai Temple consists of five worship chambers arranged along the traditional axis of Champa religious architecture in Panduranga. The three main chambers are located at the rear: the central chamber venerates King Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha); the left chamber honors the Cham queen Po Bia Som, along with two Patuw Kut statues, considered representations of two princes according to Cham folk tradition; the right chamber venerates a Cham secondary consort, accompanied by two Patuw Kut statues symbolizing her two children in Cham religious belief.

In front are two ante-chambers, where the community performs preparatory rituals before entering the bimong (main sanctuary). These rituals include waiting, arranging offerings, adjusting ceremonial attire, and performing the steps of the Cham ceremonial protocol in Panduranga.

The statue ensemble at Po Klong Mah Nai Temple is considered a valuable example of late classical Champa sculpture. In particular, the statue of King Po Klong Mah Nai, carved from a single block of green stone, exhibits refined sculptural style, solid and solemn form. The statue depicts the king in a regal audience posture, wearing a crown that symbolizes the authority of seventeenth-century Panduranga rulers, serving as an important testament to the continuation of Champa royal artistic traditions in the late period.

Figure 16. The attribution of this crown as the ceremonial crown of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Maha Taha), the seventeenth-century ruler of Panduranga, lacks solid scientific evidence. Comparisons with the royal attire traditions of contemporary Islamic kingdoms in the region such as Islamic Champa (Panduranga), Malay, Aceh, and Java in the seventeenth century show clear differences. These dynasties typically used turbans (serban), fabric hats, or lightweight symbolic crowns, with minimal large-scale ornamentation or heavy carving, reflecting Islamic principles of restraint in expressions of authority. In contrast, this crown has a heavy structure, is covered in gilded metal, features dense scrollwork patterns, and is embedded with numerous colored stones, aligning more closely with late Khmer-Angkorian traditions. This distinction supports the conclusion that the object does not belong to the Islamic royal attire system of King Po Klong Mah Nai in early seventeenth-century Panduranga. Photo: Collected.

Figure 17. Although this crown is currently presented as the “crown of King Po Klong Mah Nai,” an analysis of its form, artistic style, religious context, and historical sources provides no scientific basis to identify it as the ceremonial crown of King Po Klong Mah Nai (Maha Taha), the seventeenth-century ruler of Panduranga. The object should be understood as a ritual or symbolic cult artifact, created in a later period to serve the deification of the king’s image at the temple, rather than an original historical object of the dynasty. This critique recommends that the scientific advisory board revise the display label and classification of the artifact, and conduct further research to clarify the ritual history and deification practices of Champa kings. Photo: Putra Podam.

Figure 18. According to the Binh Thuan Department of Culture, this object is presented as a gold hair bun ornament of Queen Bia Som, crafted with exquisite technique and characteristic of late Champa ceremonial jewelry. It may have been a type of ornament reserved for women of the royal or high noble class, used in court and religious ceremonies. However, there is insufficient scientific evidence to confirm that it was a personal item of Queen Bia Som, the principal queen of King Po Klong Mah Nai. No historical texts or inscriptions directly associate the object with her, and the artifact lacks clear archaeological context to identify a specific owner. Moreover, gold hair bun ornaments were not unique items but a common form of Cham royal jewelry, likely worn by multiple queens, consorts, or noblewomen. From a historical and archaeological perspective, attributing the object to a specific historical individual without verified evidence violates scientific principles. The most appropriate and cautious approach is to identify the artifact by its type, date, and cultural context, rather than linking it to Queen Bia Som based on conjecture or oral tradition. Therefore, it can be concluded that the object is a Cham royal gold hair bun ornament of high historical and artistic value, but its attribution to Queen Bia Som remains unverified and should be reconsidered. Photo: Putra Podam.

Every year, the Cham Ahier (agama Ahier) community belonging to the Ahier group who venerate Po Allah while maintaining layers of indigenous Champa belief continues to hold numerous traditional rituals at the Po Klong Mah Nai Temple. Ethnographic studies by A. Cabaton and G. Moussay document a reconciliation between Islam and royal cult worship in Cham Ahier religious life, explaining why a temple dedicated to a Cham Muslim king has been able to maintain uninterrupted ritual practices.

According to records of the Binh Thuan Provincial Department of Culture, certain objects introduced as the “treasures of Po Klong Mah Nai” were once kept at the house of Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them in Phan Ri (1911-1995). However, comparison with ethnographic sources indicates that these items were in fact entrusted to Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them for safekeeping by a Churu descendant amid the social upheavals of the second half of the twentieth century, rather than being royal heirlooms of the Po Klong Mah Nai dynasty (reigned 1622-1627). Twentieth-century ethnographic sources further confirm that the royal heirlooms of the Po Klong Mah Nai or Po Rome lineage were transmitted internally within the Churu Cham Islamic community in Panduranga and were not passed on to other ethnic groups.

Within the Cham community, a legend occasionally circulates claiming that Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them was the “last Cham princess” and therefore entitled to inherit the treasures of Po Klong Mah Nai. This argument, however, lacks historical foundation. First, in terms of chronology, Po Klong Mah Nai ruled in the early seventeenth century (1622-1627), whereas Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them was born in 1911 and died in 1995 nearly three centuries later; consequently, she could not have been a direct descendant of that dynasty, nor could she have possessed original royal heirlooms belonging to the king’s Churu lineage. Second, according to the Panduranga chronicles and the analysis of Po Dharma, Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them could only have been a descendant of local leaders of the Thuan Thanh garrison period appointed by the Nguyen court from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, such as Po Saong Nyung Ceng (Nguyen Van Chan, 1799-1822), Po Klan Thu (Nguyen Van Vinh, 1822-1828), and Po Phaok The (Nguyen Van Thua, 1828-1832). These figures were administrative officials within the new political system of the Nguyen dynasty and bore no blood relationship to the Churu royal house of Po Klong Mah Nai (1622-1627) or Po Rome (1627-1651).

Therefore, the assessment by the Binh Thuan Provincial Department of Culture that the objects kept at Mrs. Nguyen Thi Them’s house were “treasures of Po Klong Mah Nai” is inconsistent with historical evidence, does not conform to the tradition of royal heirloom preservation within the Churu Cham Islamic royal lineage, and requires correction to ensure accuracy in the interpretation of Champa heritage.

Figures 19, 20, and 21. Several objects regarded by the Binh Thuan Provincial Department of Culture as being associated with King Po Klong Mah Nai. Source: Collected.

During the reign of Po Klong Mah Nai (Po Mah Taha), historical sources indicate that royal authority in Panduranga was profoundly influenced by Islam, particularly by the Melayu Aceh Islamic tradition, which had interacted with Champa from the fifteenth century onward. Certain Cham oral traditions, together with the writings of French scholars such as Étienne Aymonier and Georges Maspero, acknowledge that from the seventeenth century the majority of the Cham community in Panduranga had embraced Islam, especially among the nobility and the military groups directly shaped by the regional Indian Ocean Muslim merchant networks. Aymonier recorded the dense presence of Cham Islamic communities in Panduranga from the seventeenth century, with Islamic religious institutions becoming more firmly established there than in northern Champa, which had fallen earlier.

The introduction of Islam into Champa, although largely peaceful, initially generated significant ideological tensions. This stemmed from the fact that Champa still retained a strong Hindu legacy a religion that had dominated for many centuries and only gradually declined as major Hindu power centers in Southeast Asia such as Majapahit, Angkor, and various Malay-Hindu polities were replaced by emerging Islamic kingdoms like Malacca and Aceh in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This transitional phase from Hinduism to Islam deeply fragmented Cham society, most notably in the opposition between Hindu Cham and Muslim Cham communities.

At the level of social thought, Islam brought about a major spiritual transformation for the inhabitants of Champa: a shift from animistic beliefs and a traditional polytheistic system to the monotheistic faith centered on Allah, the single Supreme Being governing the universe. This change was not merely religious but also represented a transformation in cognitive and cultural paradigms, as devotion turned toward one transcendent God rather than a network of local deities. According to Po Dharma, this process “produced a profound Islamization in Panduranga, reaching its peak in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”

Nevertheless, the Islamization of Champa was not without adverse effects. Although Islam in Champa was “localized” (Islam localisé) to accommodate indigenous traditions, certain strict Islamic doctrines still influenced spiritual and social life, particularly concepts of predestination and obedience to authority. The emphasis on predestination inadvertently became a political instrument in the hands of the Champa ruling elite, used to demand loyalty from subjects, maintain social order, and curb popular resistance. This fusion of religious doctrine with feudal mechanisms contributed to a degree of social fatalism among segments of the Cham population.

Religious polarization between Hindu Cham and Muslim Cham became increasingly pronounced as the Panduranga dynasties faced continuous military and political pressure from Đại Việt between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The final wars between Champa and Đại Việt (notably the events of 1692, 1720, and especially the upheavals of 1832-1835 under Emperor Minh Mạng) forced large segments of the Muslim Cham population to migrate to Cambodia, Kelantan, and Terengganu (Malaysia) in order to escape repression and social restructuring imposed by the Huế court. Many of these Muslim Cham groups later formed Champa diasporic communities in Châu Đốc, Phnom Penh, Kampong Cham, Battambang, Kelantan, and Terengganu places where strong Cham Islamic identities are still preserved today.

This migration was not solely a form of wartime refuge but also reflected the continuation of Cham maritime traditions and regional trade networks. According to oral accounts among Cham communities in Kelantan, many Cham lineages in present-day Malaysia and Cambodia still preserve genealogies recording that their ancestors lived in Panduranga until the outbreak of wars with Đại Việt.

The reign of Po Klong Mah Nai thus unfolded during a period of profound transformation, when Champa shifted from a society divided between two major ideological systems toward an era of intense Islamization, triggering social, religious, and migratory changes that have had lasting impacts on Cham communities both within the homeland and across the diaspora.

Related links:

1. Petition Requesting the Correction of Historical Information at the Po Klong Mah Nai Heritage Site

2. Kiến nghị hiệu đính thông tin lịch sử tại di tích đền Po Klong Mah Nai

3. Po Klong Mah Nai truyền ngôi cho Po Rome (Nik Mustafa)

4. King Po Klong Mah Nai abdicated in favor of Po Rome (Nik Mustafa) (English)

5. Sở Văn hóa Bình Thuận đưa thông tin sai lệch về Po Klong Mah Nai

6. Bà Nguyễn Thị Thềm không phải hậu duệ của vua Po Klong Mah Nai

7. Putra Podam video: Vua Po Klaong Manai vị vua Islam (Hồi giáo)

8. Putra Podam video: Tháp Champa: Đền thờ Po Klaong Mah Nai

9. Video Đài Bình Thuận (BTV): Lễ phụng tế Po Klong Mah Nai ???

References

1. Aymonier, Étienne. Notes sur les Chams et leur religion. Paris: 1891.

2. Cabaton, Antoine. Essai sur la langue cam. Paris: 1901.

3. Maspero, G. Le Royaume de Champa. Paris: 1928.

4. Parmentier, Henri. Monuments chams de l’Annam, Tome I. Paris: Publications de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), 1909.

5. Coedès, George. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1968.

6. Moussay, Gabriel. Dictionnaire Cam-Français. Saigon: 1971.

7. Po Dharma. Le Panduranga (Campa) 1802-1835. Paris: École Française d’Extrême-Orient, 1987.

8. Po Dharma. L’histoire du Campa. Paris: 1989. Xem thêm Pierre-Bernard Lafont (ed.), Champa et le Monde Malais. Paris: 1995.

9. Mohd. Zamberi A. Malek. The Malay-Champa Historical Relations. Kuala Lumpur: 1995.

10. Sakkarai dak rai patao (Biên niên sử các vua Panduranga). Bản chép tay lưu hành trong cộng đồng Cham; đối chiếu theo Po Dharma, Chroniques des rois de Panduranga, EFEO Archives.

11. Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn. Đại Nam Thực Lục. Bản dịch Viện Sử học, Hà Nội.

12. Bộ Văn hóa - Thông tin Việt Nam. Quyết định số 43/VH/QĐ ngày 7/1/1993 về công nhận di tích lịch sử và nghệ thuật quốc gia.